Gender in the Workplace Part 2

A Nonbinary Individual’s Foray into Corporate A.V.

I think my boss gave up on trying to remember my pronouns.

It started about two weeks in. During the hiring and application process, as well as preliminary training, I could tell he was trying. But after seeing how my other coworkers could skirt past it, I suppose he figured he could, too.

I don’t mean any harm to any of my coworkers, I would like to point out. The two 62-year-old guys’ guys can’t be held to the same standard as I could hold a Gen-Z’er with similar political ideologies to me. I don’t hold it against them, as I’m simply chronicling my experience in this line of work. But, and I mean this from the heart, I don’t want to work somewhere where I’m not seen as myself.

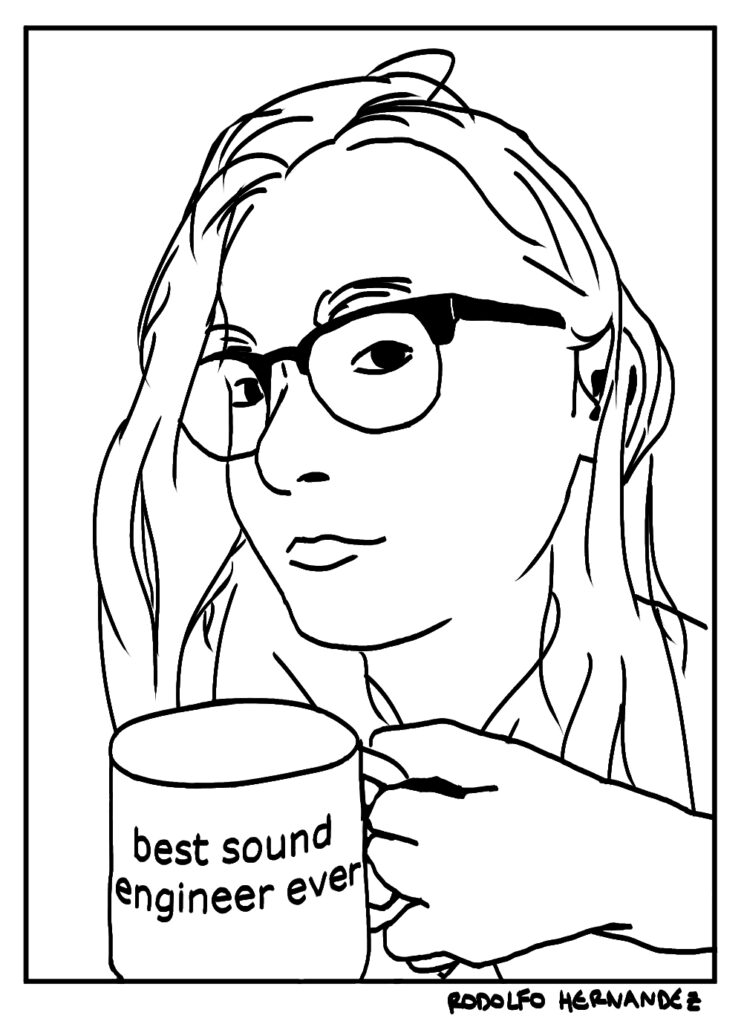

My entire A.V. team consists of men, with one exception. Since my transfem coworker quit, there’s only myself and one woman who bucks the trend. She’s a 26-year-old with a music degree and left-leaning views and sees herself as on the older end of Gen-Z. As you can imagine, she’s been my light in the dark during the harder days. She’s fairly consistent with getting my pronouns correct, as well, which is encouraging, especially seeing that I don’t think anyone else has tried.

I have a pin on my messenger bag that reads, in all capital letters, “MY PRONOUNS ARE THEM/THEY.” I’m not entirely sure why the order is them/they instead of they/them, but it’s an important object to me either way. I bought it at Lancaster Pride, back in 2017. I was just figuring myself out at the time. I waited until my friends were out of sight, and then purchased it with cash while nobody was looking. There was a sense of shame about it that I don’t feel anymore. But anyway, I bring this bag with me to work every day. And, believe it or not, this has caused some issues.

I’ve had three different coworkers try to “debate” me about my gender identity like each man somehow knew better than I did.

Those conversations were weird, to say the least, and deeply uncomfortable. The first of which was with an anti-mask climate change denier, so you can imagine how that went. His father and grandfather before him were upper-class white rural farmers. There was a disconnect in the way we were raised, and I think that that makes conversation with him trying at times. Mainly because he’s a man who doesn’t listen to science, not unless it supports his already deeply ingrained beliefs. In all his wisdom, he told me there are only two sexes, like this was somehow news to me. It was as if he genuinely believed I’d gone through over twenty years of life without knowing about chromosomes, and that they were the only basis of gender identity. I mentioned intersex individuals, and then he proceeded to ask me if I was one. Since I am not, he told me that I must be a woman.

The second conversation was with an intelligent guy from Baltimore, about in the same age range as the first fellow I mentioned. We were sitting in a Vietnam War memorial service and luncheon, held in the event center we work at. He and I were stationed at a tech table off to the side. I always really respected this coworker, as he’d had the most experience in the A.V. business. We were talking about history, and eventually, that conversation evolved into talking about the history of race and gender in the Vietnam War era. He is a black man, and he was specifically talking about the terminology used at the time. He mentioned that African American wasn’t a term they used at the time, and he expressed his distaste for it, seeing as he’d never even been to Africa. He was simply American, and he was black. The intersection where those two adjectives met is how he described himself– an intersectional identity.

He then brought up how the way he wore his hair, at the time, drastically changed others’ perception of him. On this topic, I mentioned that I felt the same. People didn’t readily assume I was nonbinary until I cut my hair. I enjoyed wearing my hair in long blonde curls, but it was easier to be nonbinary with short hair. People were able to clock me as queer, and it made the constant coming out a lot easier for me. That’s one thing to note about nonbinary identities– there’s a constant need to come out to be recognized. Hence the pins: it’s a way to be seen and respected without having to constantly address my identity. It’s a good thing, too, because that gets old quickly. My coworker then mentioned the pin on my bag and asked me what being nonbinary meant to me. I was taken a little aback by this, but given the deep nature of our conversation, I answered.

“To me, gender is a protest,” I said, trying to boil down years of study, a complex understanding of gender constructs, and Western societal tradition into one simple sentence. “I was told that, due to something about my body that I can’t change, I had to fit into a certain mold. I had to only spend time with girls, I had to worry about hiding my acne with makeup constantly, and I had to dress a certain way that identified me as a member of a certain sex. Girls were taught in school that they must hide their shoulders, lest they cause a man to stumble. Girls were told they should stay in the kitchen and live to serve men. It’s been less than a century since women were granted the ability to work, and even now wages don’t line up. We are all people, all the same, and I reject the idea that our anatomy somehow makes us inherently different. I believe, deep down, that we’re all the same species, and that our genders aren’t as important in our lives as society has taught us to believe.”

He then changed the topic to religion, and how his religion separated men and women. I felt my eyes gloss over as I listened to the same argument I’d heard a million times, that somehow, the creator made women the submissive, subservient sex. And you know what? I just don’t think that’s true. But agree to disagree, right? It was hurtful, but I wasn’t going to refute his opinion on the “debate” of my identity. He has worked here for over a decade. I’m not going to lose my job over this.

Y’know, this sort of thing doesn’t happen when I’m working in theatre. Before this A.V. gig, I was working at the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival as a sound engineer, just outside of Allentown, PA. It was such an eye-opening experience as to what the workplace could be. We were on a tight schedule, but my coworkers and I were always on the same page. I was left in charge of things once I felt comfortable, and there were always other LGBTQ+ individuals not too far away. I felt like a respected and responsible member of the team. It’s weird how something like respect can significantly alter the work environment. Here, in the A.V. position I hold now, I don’t feel as confident or self-assured. When working with coworkers here, I am talked over and talked down to, as if I don’t understand the things I studied at a collegiate level. I am very infrequently scheduled onboard op positions, despite that being my strength, as there’s always a guy “manning” the board. Even though my female coworker is in a managerial role, she’s still treated as if she were at the bottom of the totem pole.

So, I beg the question, is sexism the root of transphobia? In my experience, well. It’s starting to seem so.