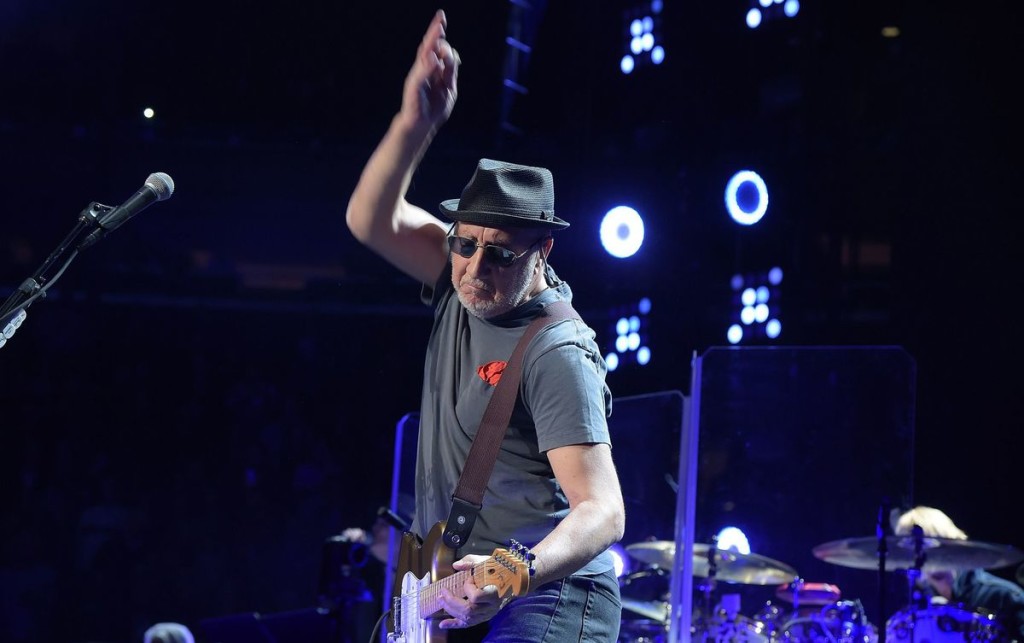

Trevor Waite – On Monitor Teching and Mixing Monitors for The Who

Trevor Waite has been part of the monitor team for The Who since 2007. He has worked along side The Who’s two monitor engineers Simon Higgs and Bob Pridden. Trevor has recently taken over for Bob Pridden, who has recently retired from the road and has mixed monitors for The Who and Pete Townshend for 50 years. Trevor has some big shoes to fill but with his experience working with The Who and his positive attitude he will step up to the occasion. Trevor was kind enough to share his experiences, advice and tips on teching with us.

Trevor Waite has been part of the monitor team for The Who since 2007. He has worked along side The Who’s two monitor engineers Simon Higgs and Bob Pridden. Trevor has recently taken over for Bob Pridden, who has recently retired from the road and has mixed monitors for The Who and Pete Townshend for 50 years. Trevor has some big shoes to fill but with his experience working with The Who and his positive attitude he will step up to the occasion. Trevor was kind enough to share his experiences, advice and tips on teching with us.

What is your background and how did you get your start?

My career started out as a part time job in college. Prior to college, I was an electronics technician in the US Navy, serving aboard USS John F Kennedy (CV-67). After my 4 years (during Desert Storm), I left the Navy to pursue a degree in Electrical Engineering at Rochester Institute of Technology, which proved to difficult for my simple mind, and ended up dropping to Electrical Engineering Technology (essentially, an over-trained technician).

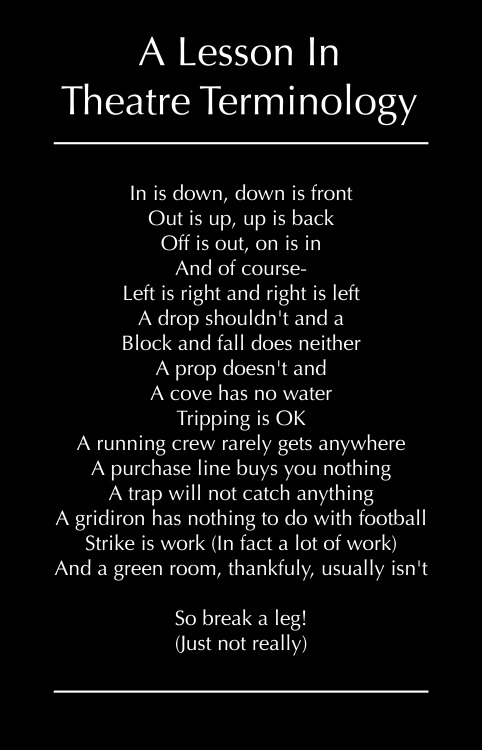

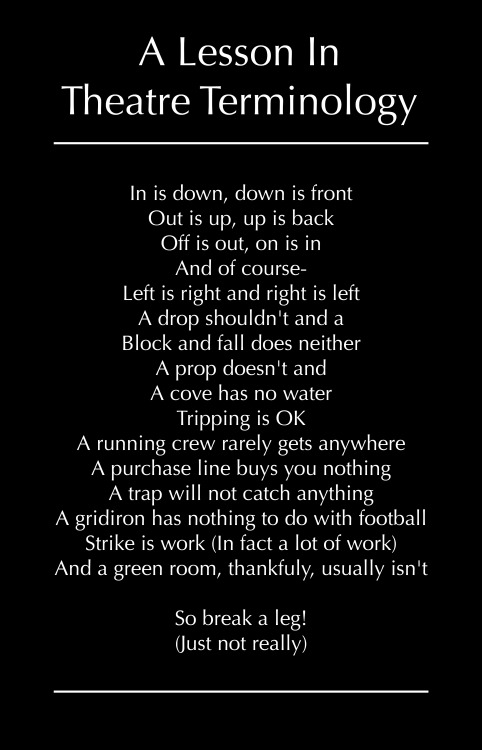

The college had a small production company on campus that took care of stage, lights and sound for the smaller gigs, and provided labour for the larger acts that came through. Tech Crew, as it was called, was set up such that the boss taught the first batch of student employees, and they continued. It was brilliant. In order to advance, one had to get signed off on even the most basic of skills…cable coiling. Probably the best way to learn. As I got better, I managed to start teching at a local club. This helped hone my troubleshooting skills, as some of the gear needed attention.

After college, I managed to get a couple of jobs in my field of study, but quickly got bored with it. My final day of working a 9 to 5 happened after getting to run monitors for Ted Nugent at that same club. I quit working in my field, and followed my passion. I continued with a regional company, but still wanted more. I sent out resumes to multiple sound companies, and only got one response. But that response launched an amazing career. Eighth Day Sound gave me a chance, sent me out on Prince with two really good engineers and another great technician, all of whom taught me the ropes of touring. 14 years later, here I am, loving every minute of my career and meeting some incredible people and the bands they work for.

Questions from SG Members:

When people ask what I do, I never know what to say because there are so many terms that can describe what abilities and knowledge I have. I didn’t even realize there were system techs. for Monitors and FOH until I read a blog on SoundGirls.org. I know that everything I have learned about sound and signal processing/electronics etc. would easily make me by definition a “system tech” already, but does that mean I should consider myself a sound engineer and technician?

There is a major difference between a sound technician and an engineer. I consider myself a very good technician, but an average engineer. I am fine with that, because a good engineer has a very unique gift…that of above average hearing. While I can hear well enough to EQ a monitor to get very loud without feeding back, a true engineer will make it sing. Sometimes a great engineer has no idea how the electronics work to create an amazing mix, and that is where a great technician is needed. I am proud to have teched for some brilliant engineers, and have no regrets being “just” a tech.

What type of equipment do you use for room measurement? Mics, computer programs, audio interfaces, things of that nature.

When I am teching FOH, room measurements are essential to put the PA in correctly. Half the battle is getting the PA hung right. To do this, a Leica Disto capable of both distance and angle is essential for indoor venues, while an Opti-Logic range finder does very well in outdoor or amphitheater venues. Once the measurements are taken, the manufacturer of the particular PA will have a program to design the building and PA to cover it.

Once the PA is hung, I use Smaart, with a Focusrite Scarlett, to time align and get a general EQ going while running pink noise. Once the curve is relatively flat (don’t over EQ using pink noise), listen to it with your favourite song. It may irritate the lighting guys after the 20th show, but there is a point…consistency. We need to hand our engineer a PA that sounds as close to yesterday as possible. The engineer needs consistency, and that is the tech’s primary goal.

What have you worked with in the past and how does it compare to what you use now and how you are able to do your job now?

I got into the industry when there were no computer programs to design PAs. We would stack and adjust chains on a trial by fire basis until the PA looked like it should cover the room. Experience helped make fewer trips up and down as the PA was adjusted. These days, you can accurately design a PA without stepping foot in the venue. CAD drawings are available for most venues, and the prediction software for most major PAs can either directly import these drawings, or can easily be deciphered. Then the PA can be simulated until the system tech is happy with the virtual coverage.

Then there’s the consoles. The industry has come a long way in the time I’ve been in it. If we knew we were going to work with a band again, we would have to manually chart every knob and fader position, which was painstakingly slow. Now with digital consoles, simply throw your USB key in from the last show, and off you go.

What sort of ear training should be done to help in tuning monitors?

The only way to learn your frequencies is to make a system feed back and listen. I learned by rote. After hearing a frequency enough times, you will know it the next time you hear it feeding back. Once the feedback is done, learn the sound of your voice. This may sound strange, but try this. Record your voice, then play it back. It is different than you perceive it to be. Therefore, know what you should sound like, then make the monitor sound like you. There you have it…safe then sound.

Have there been any helpful books or training courses that you would recommend?

I got very lucky that my college had a production company that handled the smaller shows, and provided labor for the big acts that came through. Essentially, The boss taught the first batch of students, then had them teach the new hires every year. You start of with the very basics of coiling cables, taping cables down, proper lifting, etc. before moving on to bigger and better things. To this day, he was the best boss I ever had. Always there but never micromanaged. He is still there today.

The Yamaha Sound Reinforcement Handbook was also a very good reference.

SoundGirls.Org Questions

What are the job duties of a stage tech vs. a monitor tech?

Stage tech and monitor tech can be one and the same in some instances. When I tech for The Who, I was both, but as it was far too much for one person, I had to rely on the SL PA guy to cable up stage. In that case, the PA tech became the stage tech. This is what I believe to be the difference:

A stage tech patches the stage, gets power out to backline, and cables up the monitors. Once everything is verified to be correct, the stage tech is done until load out.

The monitor tech’s job starts long before the tour does. Once an engineer informs the company what is required, the monitor tech designs the racks, amps, stage patching and cabling to be as efficient as possible. Once on tour, the monitor tech works closely with the engineer to ensure they have what they need to keep the band happy. A good tech will go the extra mile and stand by the engineer to offer a second set of eyes to make sure all members of the band can communicate their needs to the engineer. The monitor tech is also responsible for repairs or replacements if gear goes down.

You currently tour with The Who, and have recently taken over mixing monitors for Pete Townshend, do you carry production? If so what company are you using? Do you have a dedicated tech?

Eighth Day Sound has provided control gear (monitor system and FOH console and racks) for almost all The Who shows since 2007. I have been their monitor tech since then, helping monitor engineers Simon Higgs and Bob Pridden. It has been a fantastic ride so far, and it is an amazing honour to be able to continue Bob Pridden’s work as Pete Townshend’s monitor engineer. As such, a tech has been added to take my place. Unfortunately, because of flight costs, it will not be the same tech I just trained back in the UK. And with no production day to start our next leg, I have my work cut out for me.

Before Bob left the tour the three of you had a unique system of working together, can you explain how job duties were divided up before Bob left? And how you are working now with the loss of Bob?

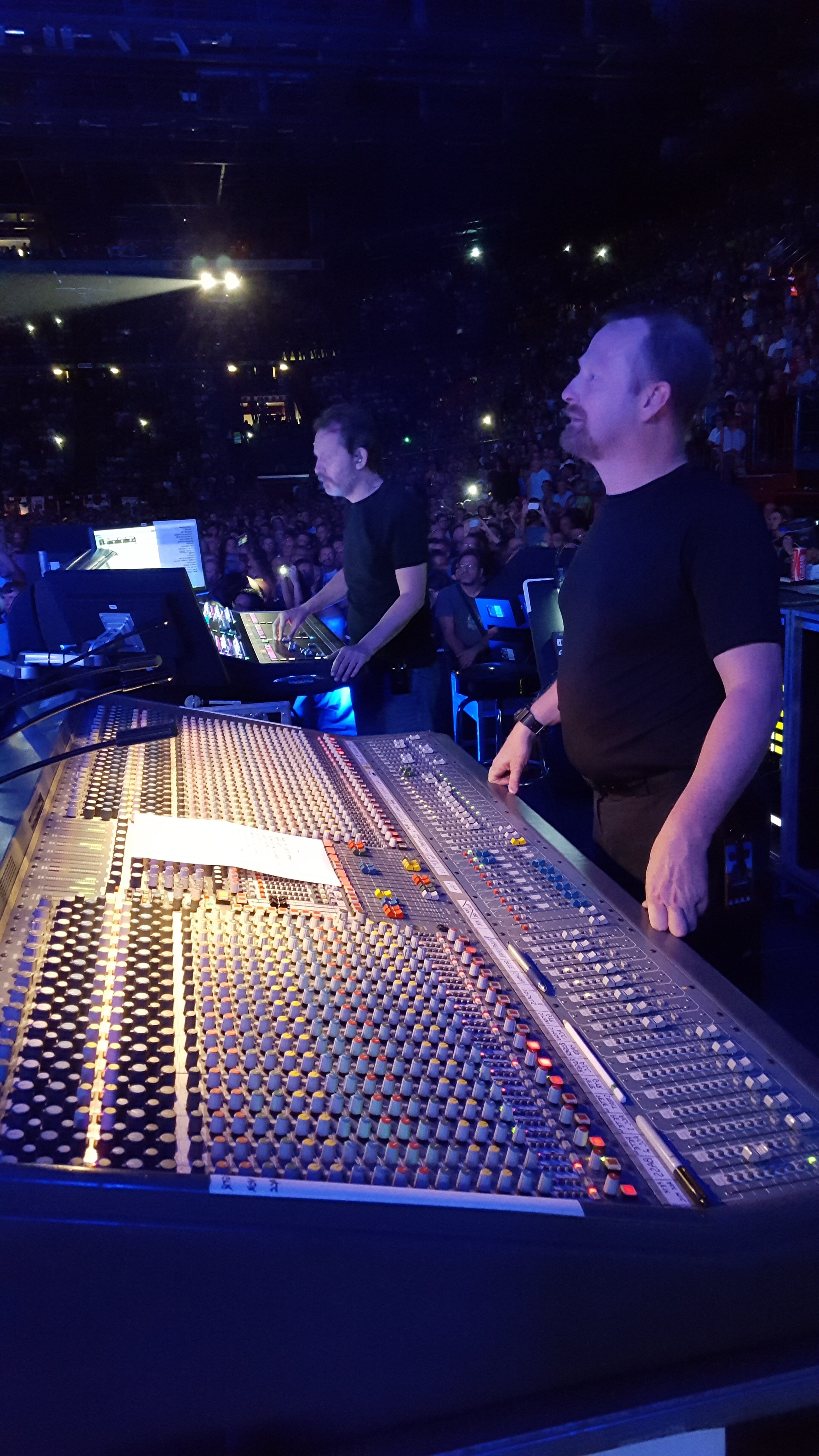

Bob traveled with the band. After being with them for over 50 years, I would say he earned that. Because of this, setting up and EQ’ing fell to Simon Higgs, who also had to frequency coordinate all of the rest of the bands’ in ears. Once monitor world was built, and stage was patched, I would put on ears and help Simon verify ear mixes, then watch Bob’s console during line check.

Once the band and Bob arrived, I would wear one ear to help Simon with the rest of the band, and listen to Bob’s cue wedges with the other ear to help Bob with Pete’s wedges. Doing this, I managed to learn key parts of songs that Pete needed adjustments during the show. I was able to help Bob keep up with Pete’s needs. Also, my eyesight was better, so I could see Pete’s requests for changes when it was almost completely dark. At the same time, while Simon was concentrating on Roger Daltrey, so I would also keep an eye out for the rest of the band and let Simon know if one of them needed something.

What equipment are using?

Currently, Simon Higgs is mixing Roger Daltrey and the rest of the band on a Digico SD7. I have inherited Bob Pridden’s Midas XL3. I have been given permission to change to a digital console, and will go with another SD7 to keep the integration simple. We will wait to make the change until after the Desert Trip shows, as there is no production day to get it right.

How do you prioritize your job duties and tech duties?

I still show up on an early call. Although I have a dedicated tech, I have always known this to be a two man job, so in the morning and at load out, I am the monitor tech, which eases the burden on the stage tech. Monitor world is huge, and therefore built on a rolling riser in the middle of the arena. I set up both consoles, and get Simon Higgs temporary power so he can start frequency coordinating when he comes in. Until monitor world is rolled into position, getting Simon started is the first priority. Once in place, I change hats and become Pete’s monitor engineer. At this point, the stage tech becomes the monitor tech, and helps Simon with verifying in ears and stands by on stage during line check to fix any mis-patches. I start EQing Pete’s wedges (something Simon used to have to do on top of everything else), and line check what is now my own console.

Teching for a FOH or Monitor Engineer requires a certain set of skills. What do you feel are important skills a monitor tech should possess?

Monitor techs should have a basic understanding of troubleshooting skills. Unfortunately, this is not taught in most sound company shops. A tech needs to know how to meter power and why, how to half split a fault (make a logical starting point to find a problem), and to know the job is not done until the truck doors close at the end of the night.

FOH and Monitor techs are often required to help the engineer achieve their vision and goals. How can tech help the engineer see their vision come to fruition?

Providing consistency under all but the most extreme conditions can go a long way to helping an engineer create their magic. If the engineer walks up to a console and everything feels the same way it did the show before (assuming that was good), then the tech has done the job properly.

What can a tech do to become irreplaceable?

I always provided the candy in monitor world. That went a long way. Otherwise, I suppose going the extra mile, as in any job, to show you are there for more than just a paycheck. I find that is easy when you like the crew and band, but it is also true if you don’t. Give each client 100%. It makes you invaluable to your company, so you will get more calls, and you can always say no once you’ve established yourself (don’t do that too often, though).

How important is it for FOH and Stage to be working together?

There’s a reason we keep them 100 feet away. They are a strange lot, those FOH people, but a necessary evil. Kidding aside, it is essential FOH and Stage work together, because the sound from either one greatly affects the sound of the other.

Some performers get distracted when there is too much low end coming from the PA, so the monitor engineer and the FOH engineer must work together to find a compromise that reduces the low end felt on stage while still giving the audience a good mix with a bit of punch. The same is true if sidefills or drum fills get too loud, or are out of time with the FOH mix. Sometimes playing with phase on certain channels can make it so the stage sound adds to the FOH sound, instead of detracting from it. FOH and Stage are intertwined, and it is very important for them to work together.

As systems become more technically advanced, how necessary is it to have training or to be certified on the different systems?

It is essential to fully understand how and why you are putting up x amount of boxes to cover a certain area. It is just as important to get the angles between the boxes set correctly, or the system as a whole reacts very differently than anticipated.

Prediction software is necessary to get the most out of whatever PA you are using, and the software requires training to understand how to use it. Manufacturers have been very good at providing training programs around the world to ensure any system tech that is flying their PA is doing it in a way consistent with the way the manufacturer intended their product to be used. This is extremely helpful when a band uses different companies on different continents. If everyone is being trained the same way, an engineer can expect a lot of consistency wherever he/she goes.

If so what training would you recommend on a large scale touring production? And for medium and small sized productions?

On all productions, training is the same. If the company one works for doesn’t offer the training, go to the manufacturer. The size of the PA doesn’t matter, as it is essential to set up a small PA properly as well as large PA. To get to the point of becoming the system tech, start at the bottom and learn cable management, PA flying in general, amp patching and how to get along with the other departments that make up a production. The best way to learn the basics is to do it (preferably with a seasoned crew to help you along).

Working in a festival situation what do you feel is important?

Speed and a proper prep. If the monitor tech has laid out everything he/she needs on stage in a logical way, setting up and striking should be fairly quick. Keep mindful of the other acts, even if they are on before you. Give everyone as much space as you can so that all get a chance to do their gig to the best of their ability as well.

What equipment and tools do you feel that every monitor tech needs to know how to use?

A multimeter. Sometimes a cable checker is very handy, especially if it’s one that has a transmitter end and a receiver end for when the cable to be tested is stretched out. Whirlwind makes a Q Box that can serve as either a tone generator or a headphone amp. A pair of headphones. And basic tools in case you need to pull gear out of a rack to troubleshoot. It would be very useful if the tech could solder, but without real training in that, I’ve seen some very poor solder skills, so I don’t recommend it for everyone.