My Love of the Guitar (Pt. 2)

Read Part One Here

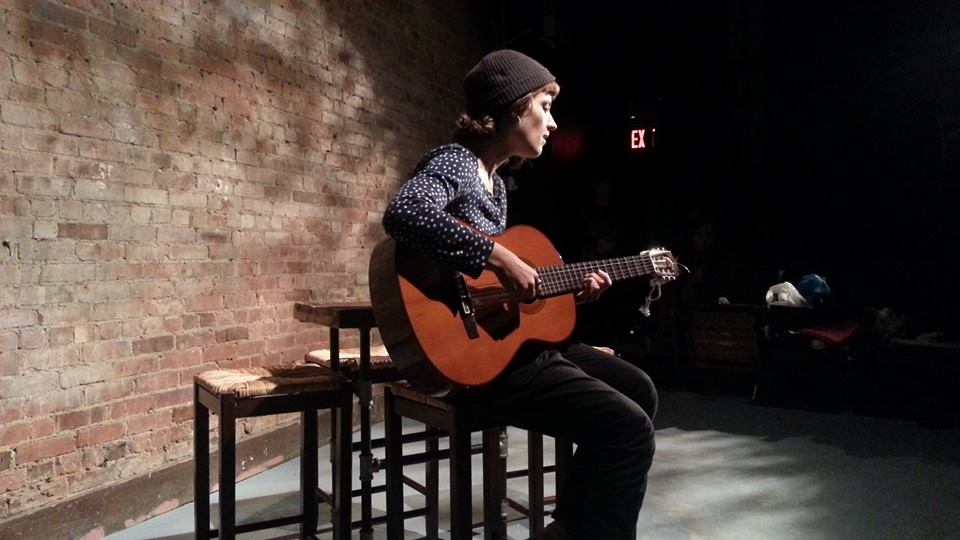

I went to an early college (Bard College at Simon’s Rock in Massachusetts), and while I was finishing up my BA thesis, I was also in my second year of private classical guitar lessons. I’d been playing for almost nine years already and was also playing the viola, and in two choirs, and music theory classes. I had a laptop, but this was before everything was done digitally, so I used my hands to write and edit and analyze notation in addition to taking notes, and editing drafts of my thesis. I write with my left hand, and I play “standard” guitar (which is to say that my left hand presses the frets and my right hand plucks the strings). My guitar teacher instructed me to practice a minimum of two hours a day, “but really six hours is more reasonable if you can manage that,” she’d suggested. Because I adored her, even with a full course load and two babysitting jobs, I practiced as much as I could. This usually amounted to three hours a day.

“If I could play in the morning or late at night, I could practice even more,” I told her. “But I don’t want to bother my roommates.”

“Ah yes, I remember those days!” She reminisced. “When I was in college, I would wake up at 4 am and put socks on my hands. That way, when I played, it was very quiet!” She said this with a twinkle in her eye. I looked at her gesturing hands and arms and realized they were perfectly oriented to hold a guitar. Even without one in her arms, she was ready to play the guitar. I wanted to be more like her. But socks on my hands? At 4 am?

All I could muster up was: “I’ll give that a try.”

I woke up earlier and drove to the soundproof practice rooms on campus. I’d set up my foot pedal, cut and file my fingernails, warm up, and set up the various pieces I was attempting to memorize. After three hours I’d head over to the library and sit in my cubicle I was allotted as a senior to read my books and take notes. For the first time, I was writing a long-form academic essay on anything of my choice. It was as exciting as it was terrifying. When the sun set, I’d pack up and drive to the next town over to babysit, where I would read, take notes, and write on the couch while a baby slept upstairs. (To this day I’ve never met this particular child. Once she woke up and I entered her room, picked her up, sang to her until she fell back asleep, and then put her back down and left the room again. But it was completely dark the whole time, so I feel this doesn’t really count as having properly met.)

After half a semester of this routine, my left arm began to hurt. I tried to give it a rest, but I was doing something with it almost every waking moment. I couldn’t help it. I hoped my guitar teacher would have a solution. I’d come to see her as a sort of wise woman; an auntie of musical persuasions.

“My left arm and hand really hurt,” I said during my next lesson. Truthfully the dull hurt had started to become a throbbing pain that was now going up to my left shoulder. “I think I’m just using this side a lot. You’re left-handed too, yeah? What do you suggest I do during this time while I’m in school and need to use my left hand to write a lot?”

She didn’t skip a beat. “Learn to write with your right hand!”

She said it with a hint of condescension like I was stupid for not having thought of it myself.

“Oh. Okay, I will have to… give that a try,” I said, disheartened. She couldn’t be serious, could she? It’s not like I chose to write with my left hand. How could it be as simple as choosing to write with my right hand?

I really did try it, but it was useless. I couldn’t write a word with my right hand, let alone notes and sentences and paragraphs.

I had to keep going the way I had been.

my first electronic (read: no guitar or live instruments) performance, somewhere in Vermont, 2010. Photo by Jane Sweatt.

After I graduated, I expected the pain to subside on its own within a few weeks, but it got worse. For the next year it was so bad there were nights I had trouble sleeping. I talked to many musicians about it. Finally, a violinist who had toured and recorded for over 40 years suggested that I had nerve damage. “You have done the same couple actions so many times, and overused certain parts of your arm in the process. The only way to experience relief is to completely stop doing those actions.”

I looked down at my right hand. I had kept my fingernails long and curved for plucking for many years. My left-hand nails were always short for pressing strings onto the neck board. I was used to typing like this, used to the difference in sensation when I would use both my hands. I loved sitting down to practice and learn new pieces, even if I wasn’t planning on being a concert player.

Could I let this go? How long would I need to stop for? Would I be okay without it? Would my college guitar teacher somehow find out and call me and berate me for not following her learn-to-write-with-your-right-hand advice? How much shame could I endure?

my first time troubleshooting Ableton Live during a soundcheck, Brooklyn, 2012. Photo by Clyde Rastetter.

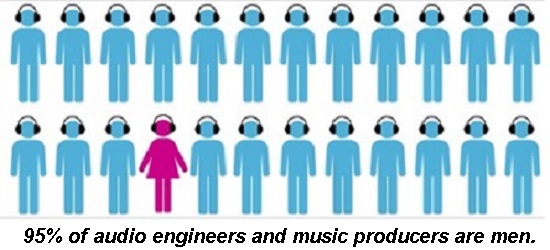

Eventually, the pain became so bad I had to stop playing for years. Sometimes I would forget the pain and would pick up a guitar for a little while and regret it later. I was so sad to not play as much as I wanted. But unbeknownst to me, my guitar time was being replaced by audio time. I was buying books, downloading programs, going to classes, and spending hours upon hours learning the ins and outs of digital audio technology. I was starting to create sounds I had never heard before, using them to create soundscapes I’d never interacted with before, and writing lyrics and melodies I’d never think up before.

Unknowingly, a new world was opening up to me.