Mixing: Down to the Details

My previous two blogs were about how to get started mixing first with the vocals, then working with the band. Once you start to feel like you’ve got mental energy to spend on other things, it’s time to zero in on the subtleties. These are the details that take the sound from a functional mix to part of the story. You as the mixer start to have room to make the show your own and add some artistic flourishes!

So what does that mean? At this point you have the vocals at good levels, you’re blending the band and pushing solos, so what else is there to do? In my very first blog, I talked about what makes a functional mix versus a good one. Up until this part of my mixing series, it’s been about functionality, so now we’re going to look at how to shape a show.

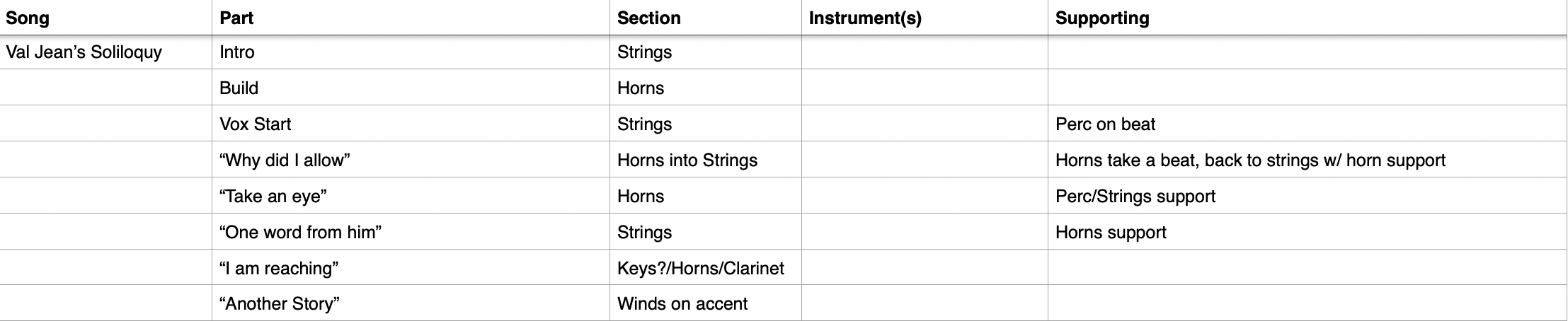

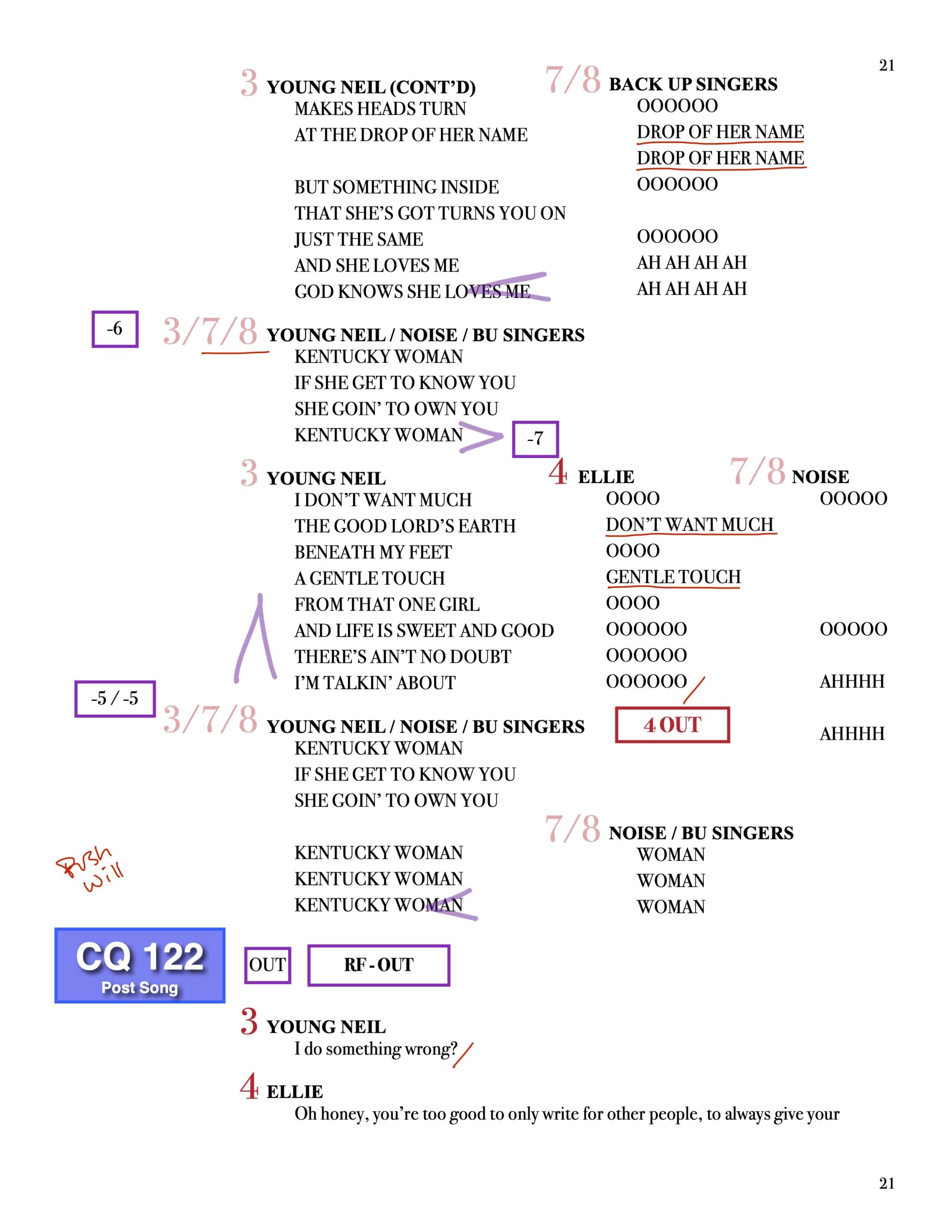

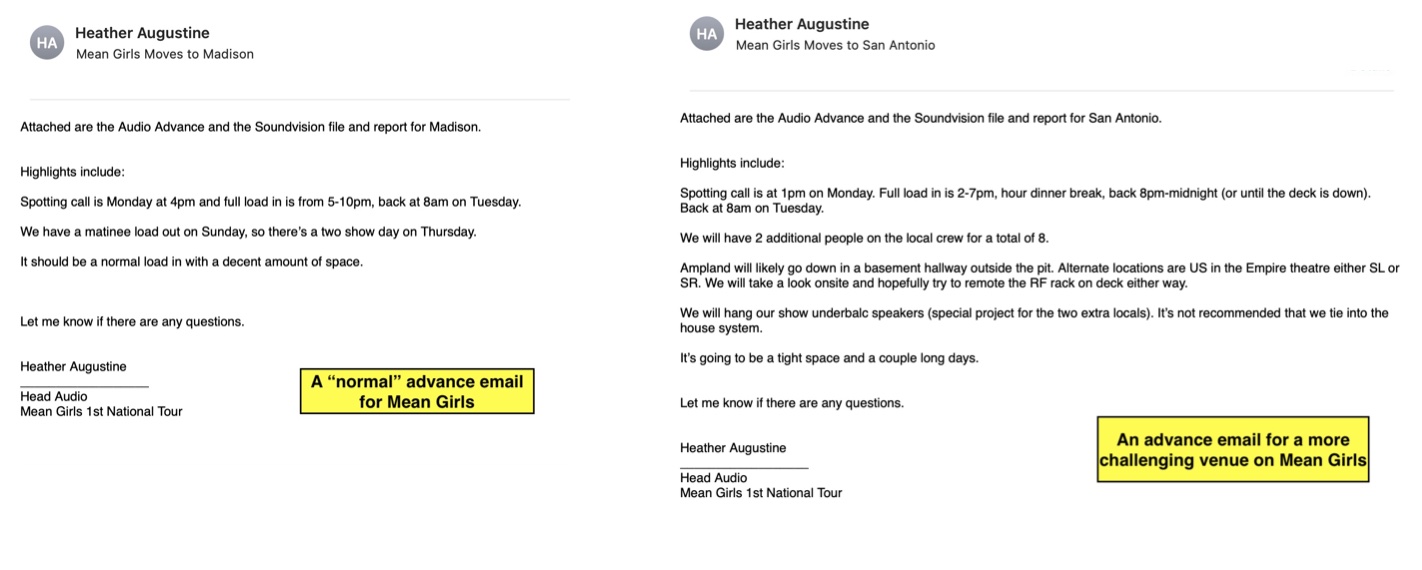

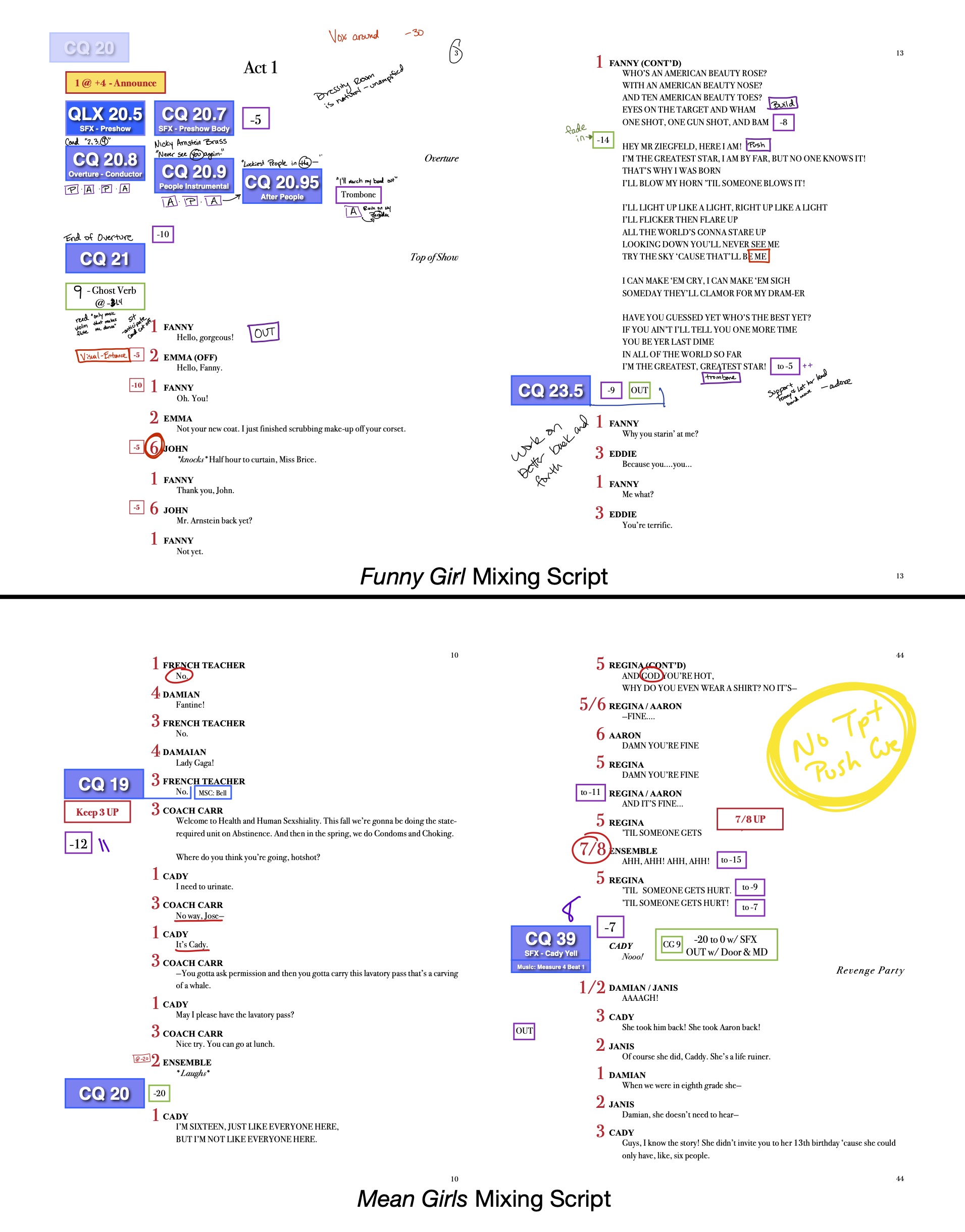

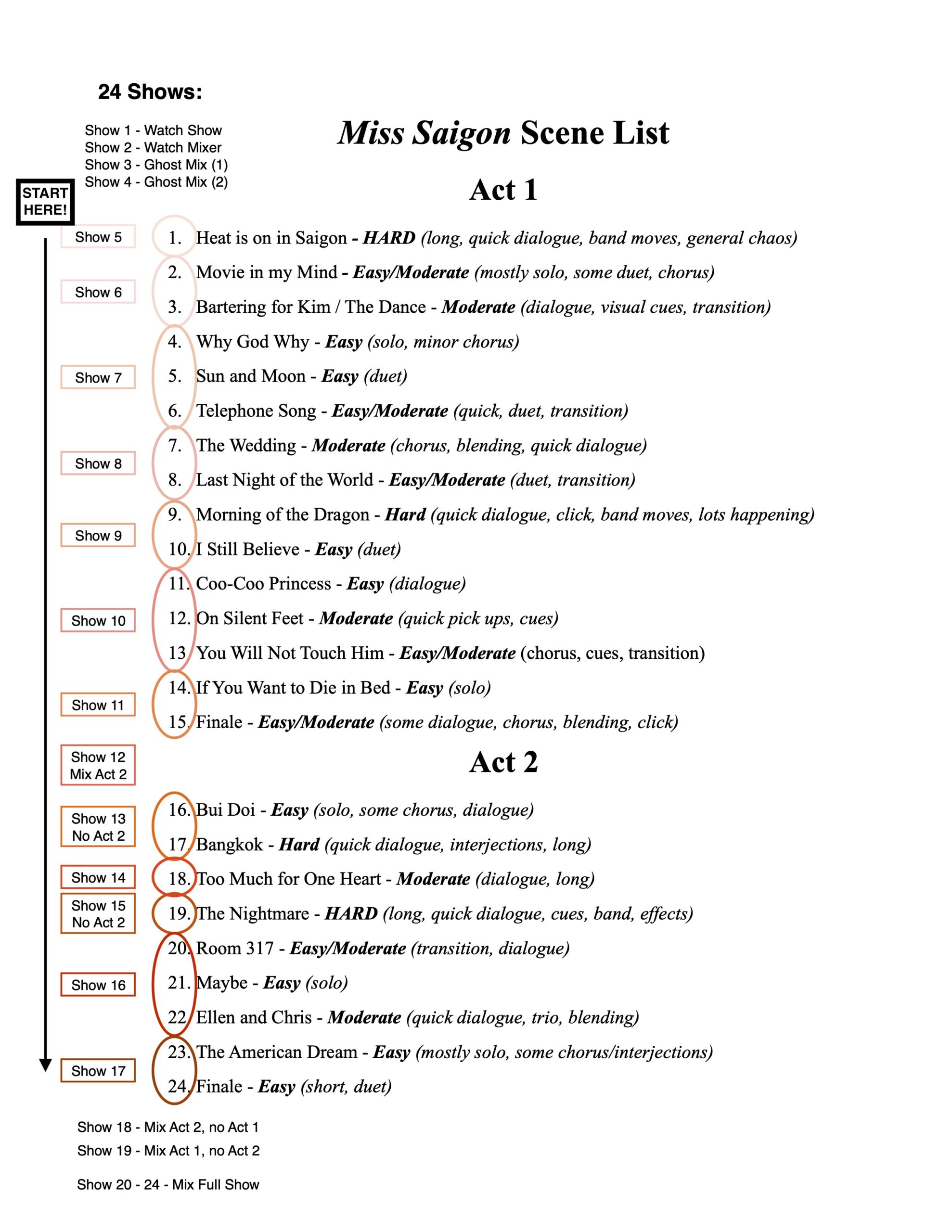

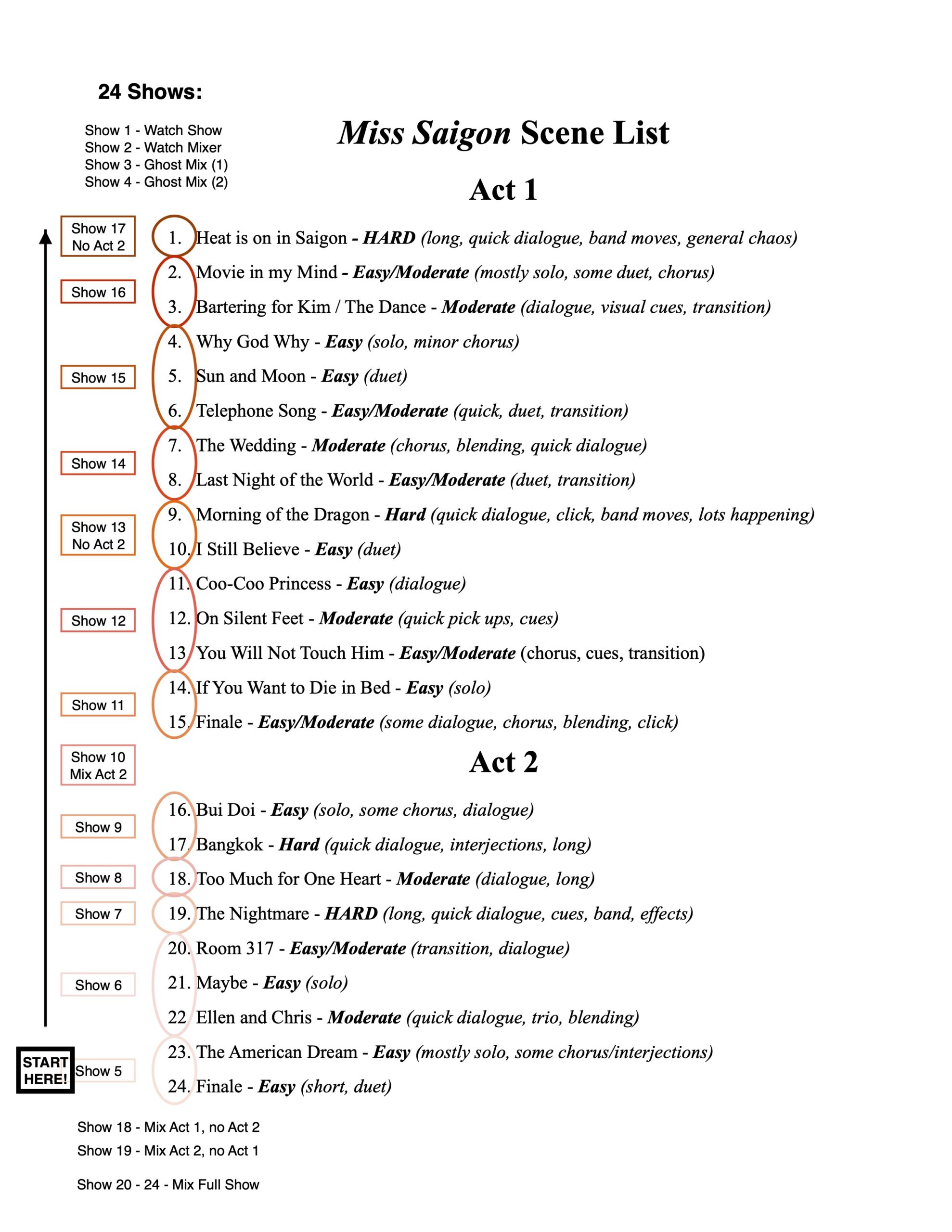

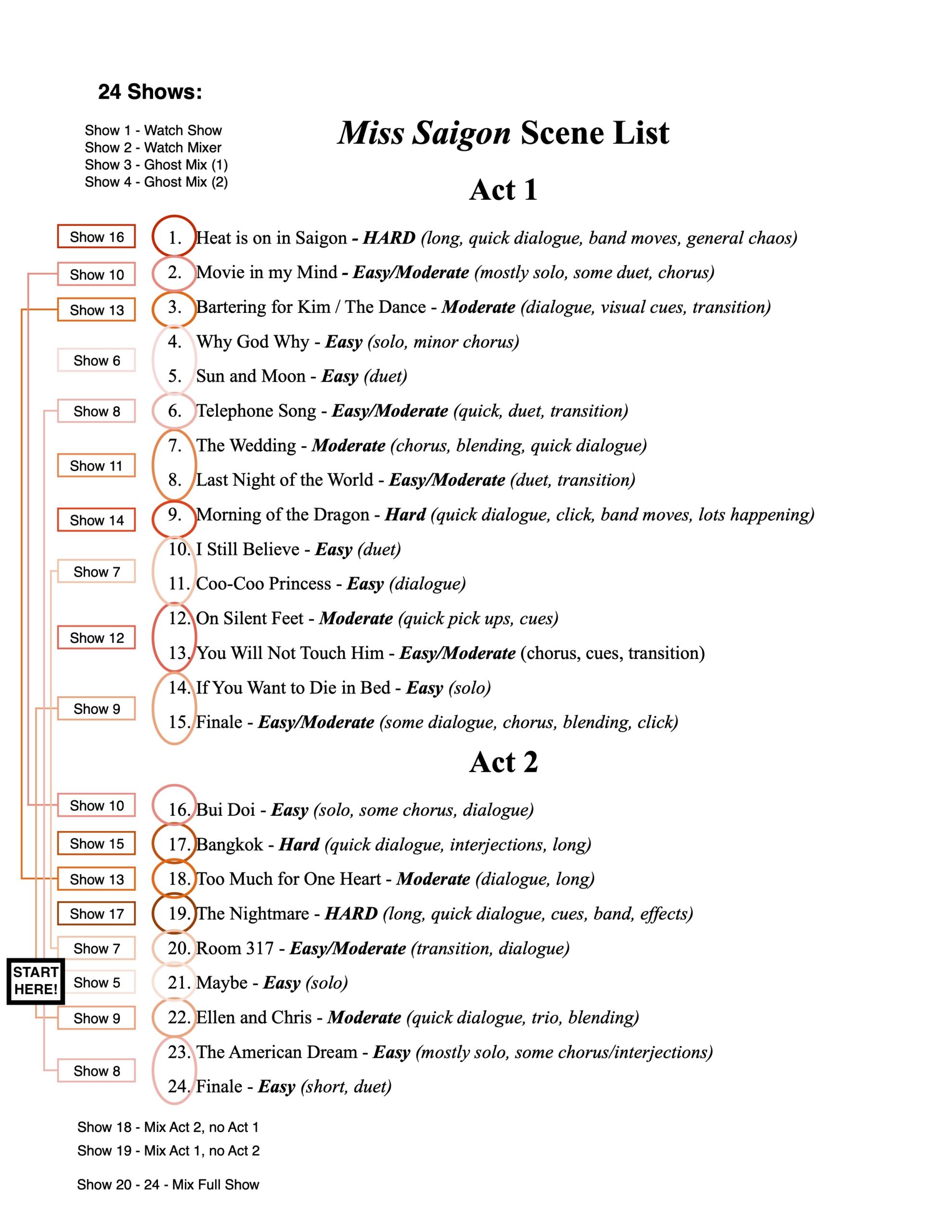

First, it’s time for an extra bit of script analysis. Some lines in a show will ask for special attention. These are plot points, setups, and punchlines for jokes, and sometimes special moments like ambient noises or ad-libs you want to highlight. Plot points are things like character introductions, foreshadowing, and establishing scene/time that might get lost. On Saigon, there is an abrupt jump three years ahead, something the characters briefly reference, so I’d try to pop those lines out to help the audience understand what was happening. On Mean Girls, when the Plastics make their entrance and each character gets a little bump as they start their introductions, especially Gretchen where we also took out the vocal verb to help make her quick, wordy bit more intelligible.

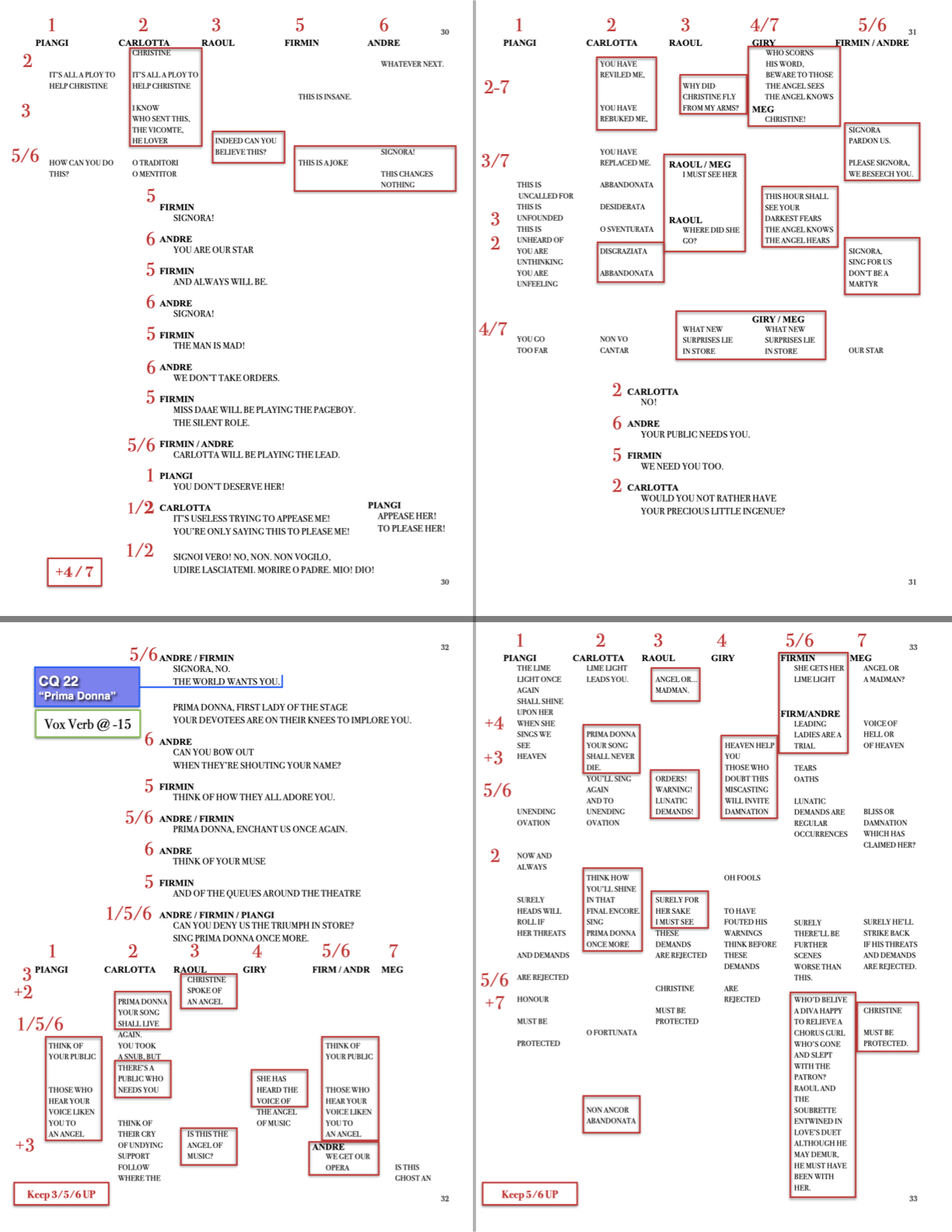

Sometimes you’ll have sections where multiple people are all singing at the same time. In Phantom of the Opera, you go from “Notes” or what we call “Managers,” a scene where the seven people on stage have rapid-fire lines back and forth to “Prima Donna” where those same people are now singing on top of each other. Your job as the mixer is to highlight the parts that are important to the story: Carlotta making her distress abundantly clear, Raoul and Mme Giry debating about the Phantom, and the managers bemoaning dealing with the aforementioned Prima Donna. You’re keeping everyone up so you maintain the musical texture that the song uses, but make sure to push the important bits just a little bit more.

This was a scene that made me fall in love with mixing every time I got it right. Managers are technical and all about getting the mics up at the right time and Prima Donna is a complete 180 into artistic blending. It’s a section where you have to bring your best every single night and I thrive on that kind of challenge. There was a while between when I learned how to do a good mix with multiple faders up to finally making it to the point where I could truly do it line by line, but that show when I finally managed it was a highlight of my early mixing days.

Back to the more technical bits, we have laugh lines. For these, you have the setup, the punchline, and the return. You typically have to push all three of these: if the audience can’t hear the set up they won’t get the joke, and then you need to signal that we’re returning to the flow of the show again with the return, usually over some last bits of laughter. Frequently, the set up comes right before the punchline, but there are sometimes the punchline will be a callback to a previous scene or act. These setups are even more important to accentuate for a later payoff.

Along with the plot, you can shape emotional volume. The goal is that the overall sound for a show is cohesive and smooth, but that doesn’t mean monotone; you’re trying to make sure that all the levels make sense in the context of the show. My favorite songs to mix are the most dynamic ones. Both “World Burn” from Mean Girls and “Little Brother” from Outsiders are great examples of songs that start very quiet and work their way all across the emotional spectrum to a big dramatic moment by the end. In both, the end wouldn’t have the same impact if you started the soloist at a normal speaking level because you wouldn’t have as much room to build. The range from deathly quiet at the start to all-out power at the end can drive the emotion home.

playbill.com Studio sneak peek at “Little Brother” from The Outsiders

As you work on more and more shows you’ll start to develop an ear for how the dynamics of the band want to shape a song, but there will always be some element of trial and error. Until you find what the band is consistently doing, there’ll be some shows where you build too fast and don’t leave yourself anywhere to go and other times when you don’t start early enough and have to rush to the end. Once both you and the band settle into the pacing of the songs and you learn how dynamic your actors are throughout a song, you’ll get more accurate and more consistent on how far and how fast you can push everything.

I had to relearn that on Outsiders. The music is different from a traditional musical theatre show and it took me a while to resist the urge to push for that big opening number or a huge finale when the music didn’t actually want to do that. For days I ended up fighting with myself on the faders, trying to get mics up hotter so I could push the band more, but reaching a point where there was only so much that I could do. I left rehearsals feeling like the mix was okay at best, and I do not like that feeling. When I got the note to pull things back and let the music sit where it wanted to, I could finally see what was supposed to be happening. When I didn’t try to force it into something it wasn’t, I didn’t have to manhandle the dynamics or push the actors too much because I was going too big with the band. That made all the difference and drew me back to take a hard look at the rest of the show to see if there were other times I was working against myself.

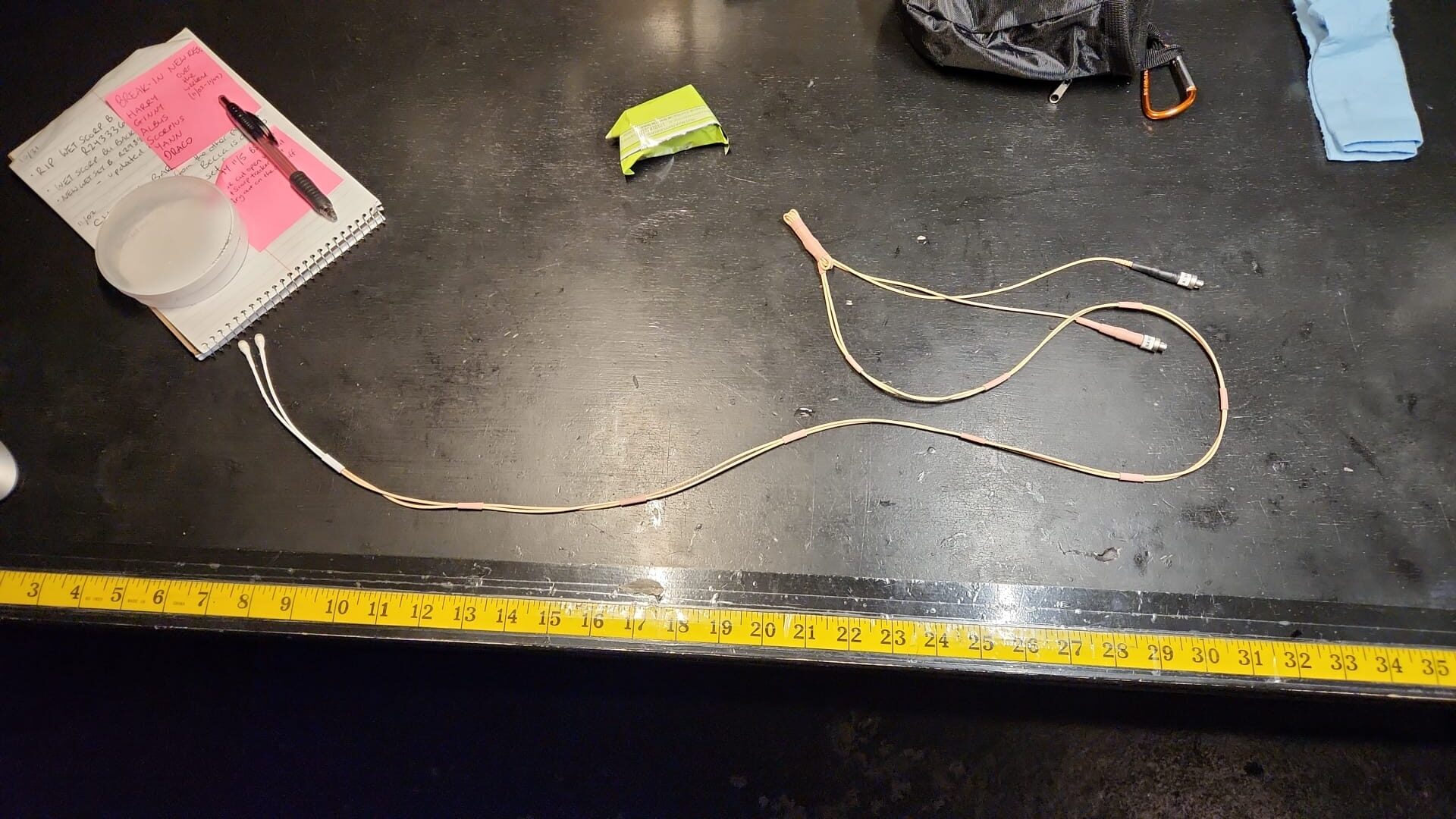

Something that will start to set you apart as a mixer is learning to correct on the fly when people are inconsistent. This could be an off day where an actor is sick or a sub-musician is in or you have someone who is just consistently inconsistent. Ideally, everyone does the same thing every day, but our job is based on dealing with the human elements and the reality is that nothing will ever be exactly uniform day in and day out. This means staying engaged and focused on the show with your fingers on the active faders and keeping your ears engaged. As you learn how an actor sounds, you can start to tell when something sounds off (they’re tired, sick, not paying attention, someone they want to impress is in the audience, etc) and even sometimes anticipate when they might go off course and you either have to give them some help or rein them in.

Sometimes those anomalies and small mistakes help you find things that work better. I’ve had times when I left the band to focus on something else and realized there’s a fun feature for someone that I want to highlight. (Or you learn that the musicians will make noise as soon as they’re done playing and it’s imperative you pull them out quickly.) On Mean Girls, our Aaron would give a little chuckle after he repeats Cady’s embarrassed “grool” (“great” + “cool”), and when I noticed he did that, I left his mic up for that extra beat. It gives his character a cute moment where you see he’s starting to fall for Cady and it draws the audience in.

Adante Carter as Aaron Samuels and Danielle Wade as Cady Heron in the 1st National Tour of Mean Girls (photo credit: Joan Marcus)

With all the talk of getting into details, this is a point where we can easily fall into the trap of over-adjusting. Sometimes for long scenes or songs, we’ll feel like we have to change something or we’re not doing our jobs. It’s hard to accept that sometimes doing nothing is the most effective path. On Les Mis, at the end of “Bring Him Home” there’s a moment when Valjean and the orchestra would start their final note. Most days I didn’t have to do anything: they did a natural resolution to the end and I’d learned that trying to push it didn’t sound right, so it was one of the very rare moments I would actually take my hands off the faders and step back. For a beat, I got to take in the picture of the stage and just breathe. To this day, whenever I hear that song, I still have a physiological response where the muscles in my back and shoulders will automatically relax because it triggers that subconscious reminder of that beautiful moment and being able to trust my coworkers and simply let go.

Nick Cartell as Jean Valjean in the 2017 National Tour of Les Miserables (photo credit: Matthew Murphy)

As the mixer you are in the unique position where you’re simultaneously in the middle of the show and the middle of the audience at the same time. Lighting and the spot ops are in booths and everyone else is backstage. You’re the only one who gets the chance to breathe with the actors and the flow of the music as you hear every reaction from the audience at the same time. Theatre is one of the few places where we find ourselves comfortable to let emotions loose in public. I love it when you can hear people start to sniffle or cry in the audience or feel the entire theater gasp as one because it means they’re with us. Shows are so much more fun to mix when that happens and digging into these details takes the audience from simply watching actors to investing themselves in stories where they care about what happens to these people.

The best thing you can learn to do is pay attention to what’s going on around you. Listen to the notes that the director is giving the actors or the composer is giving the band. Get your head out of the script and off your hands and see what’s happening onstage. The more you watch and listen, the more you’ll learn about what the vision for the show is and the better able you are to make intentional choices to further that goal. If the creatives can tell that you’re heading in the right direction, they’ll give you some leeway to figure things out. If the actors and musicians can trust that you’re there to support them even when they’re having an off-show, they’ll give you better performances. None of us work in a vacuum in this business and the sooner we learn that, the better we can make the show.