Teaching Kids about Sound

For the past ten years, I’ve been the sound faculty for a technical theatre conservatory. Students spend two years in this conservatory learning as many elements of technical theatre as possible, and generally, can declare one area as their focus. I can count on my two hands, the number of students that have come in with sound as their focus, and, by the way, less than half were women. I was always told by my students that sound is scary, or too hard, or wasn’t ever taught in high school and middle school when these students first burst into the theatre world.

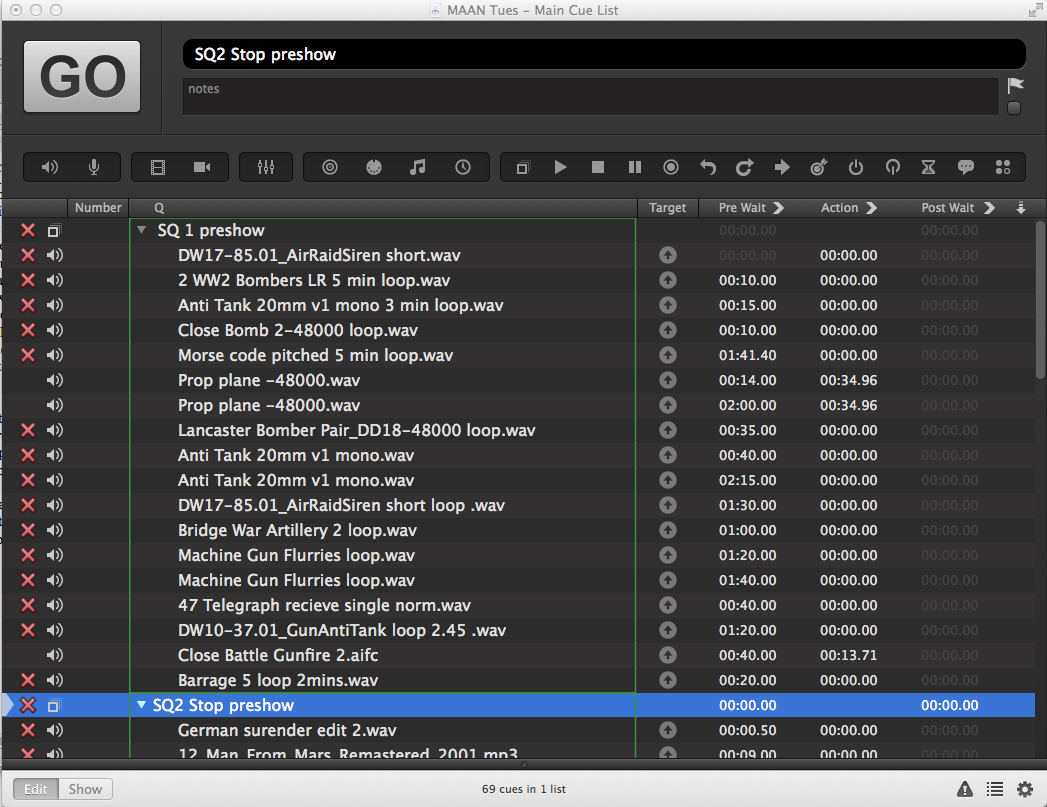

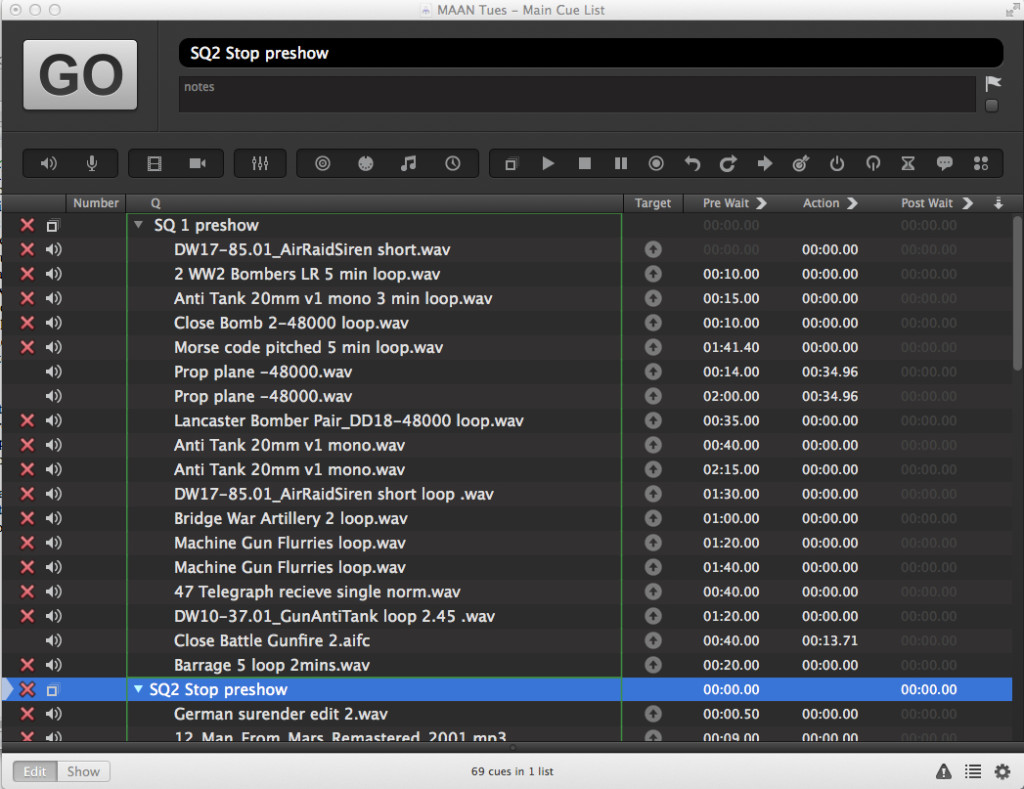

“Who ran sound for all of these musicals that you did in middle and high school,” I would ask. The number one answer? Someone’s dad. Someone’s dad would watch some YouTube videos, come in while the kids were in class, and throw together some kind of sound system that would be enough to get by. A dad and maybe the school’s technical director would run sound for the shows during the performance, and maybe let a kid stand behind the console, hit “GO” in QLab, or help put mics on other kids.

I suppose this exposure is better than nothing, but what we need to do is get kids hooked on sound from the very beginning of the process so they can understand what they’re doing instead of mimicking the few motions that they’ve been taught. This blog will feature some great resources for teaching sound to kids. If you’re the drama teacher for your school and also live in a world of “sound is scary, don’t make me do it,” this blog is for you. You don’t really need to understand everything about sound to use these resources, but checking them out might also teach you a thing or two….so, BONUS!

Elementary Years

If you’ve read any of my blogs before, you know how I feel about music and sound—they’re in a deeply committed relationship, and will be FOR-E-VER! If you want to start kids on the track to audio, get them excited about music as early as you can.

One of my favorite activities to spark a budding music mind is the “Pictures at an Exhibition” project. Modest Mussorgsky wrote this brilliant Suite in honor of his artist friend, Viktor Hartmann. The ten movement Suite was to be an aural representation of Hartmann’s work. So here’s the project: Give the kids some paper and crayons, play each of the ten movements of the Suite for them one at a time, and tell them to draw what they hear. I first did this project with 30 kindergarteners, and the results were astonishing. Without knowing the titles of the movements, they were mostly able to accurately portray what Mussorgsky was looking at when he wrote his music. This project introduces a very crucial element. It teaches kids to not only hear music but to listen. Music is a super-easy way to introduce active listening skills.

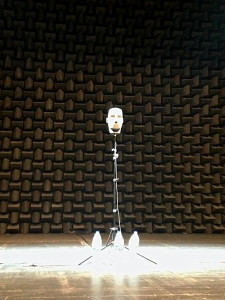

A great next step is to introduce the concept of a sonic field. Turn the lights off and clap. Now move a few steps back, and clap again. Ask your students to tell you if you were closer or further away the second time. Rinse and repeat these steps several times, and before you know it, you’ll have a room of 30 little sound engineers in the making. Check out these other great projects for tiny technicians:

Middle School Years

Middle school is the perfect time to start introducing kids to the nuts and bolts of sound. Building XLR cables is a fun and engaging project that also lets kids see the basics up close and personal. I know soldering with kids seems like a scary prospect, but if I can teach my ten-year-going-on-sixteen-year-old how to solder, so can you. Sometimes it feels impossible to teach a skill that you’ve seemingly just known forever, so remember to keep it simple, go slow, and over-explain everything. I stumbled upon this great blog about teaching kids to solder. It features lots of resources for project kits and lists everything you’ll need to get started.

You Should Teach Your Kids to Solder

Once you have successfully built your cables, let your kids experiment with connecting a microphone to a speaker, and then introduce a small analog mixer. I love to use my adorable little Yamaha MG10 for beginner projects. It’s small enough to keep kids from being overwhelmed but has enough start teaching the ins and outs of the mixing console.

A key ingredient to teaching middle school kids is being able to connect to them on their level. Incorporating their interests into your lesson will help you successfully plant those tiny seeds of knowledge. What better way to connect with middle school kids than with a cell phone? There’s a great game app called Aux B that lets users patch a sound system bit by bit. It starts simple, and throughout 40 free levels, gets pretty complicated. The game does not allow you to advance to the next level until you have successfully passed the current level and achieved blaring music through your speakers. This is a super fun way to introduce signal flow. I like to have my students race against each other on this game, and then the winner gets the glory of being the ultimate Patch Master! Here’s the link:

High School Years

High school. Here’s where we get to start having some fun with audio. SoundGym is a super fun and useful ear training program. (SoundGirls has free subscriptions, email us at soundgirls@soundgirls to receive yours) It helps users identify frequencies and the differences between them, panning, and gain differences. It’s very user-friendly, so it’s easy just to plug and play. The free version of this program does have some limitations on how much you can do, but it’s enough to be useful. I find this program the most beneficial when used on a regular basis. After all, practice makes perfect! Here’s the link:

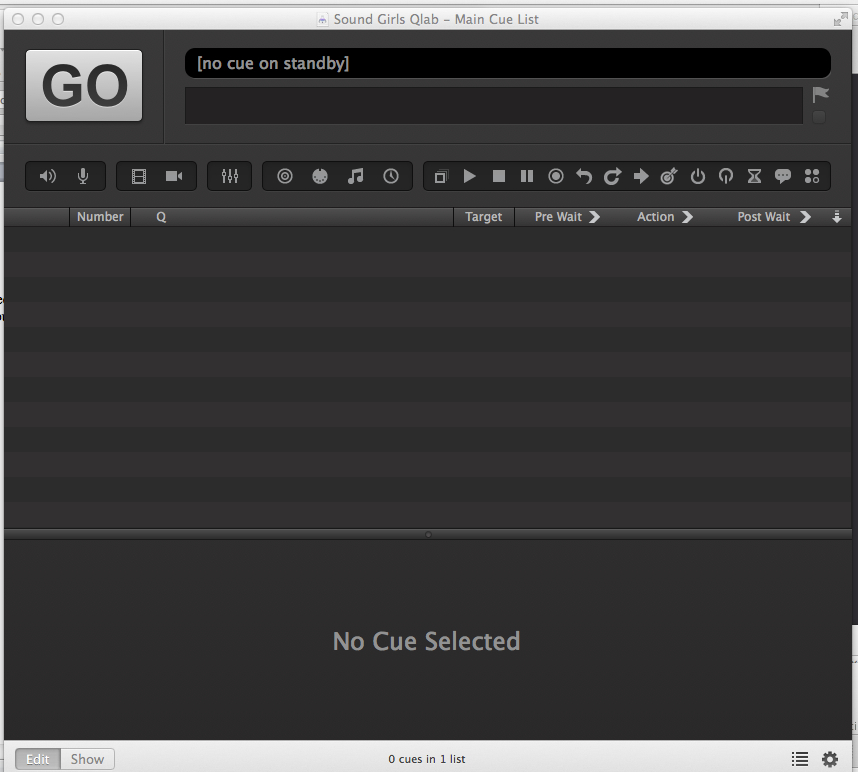

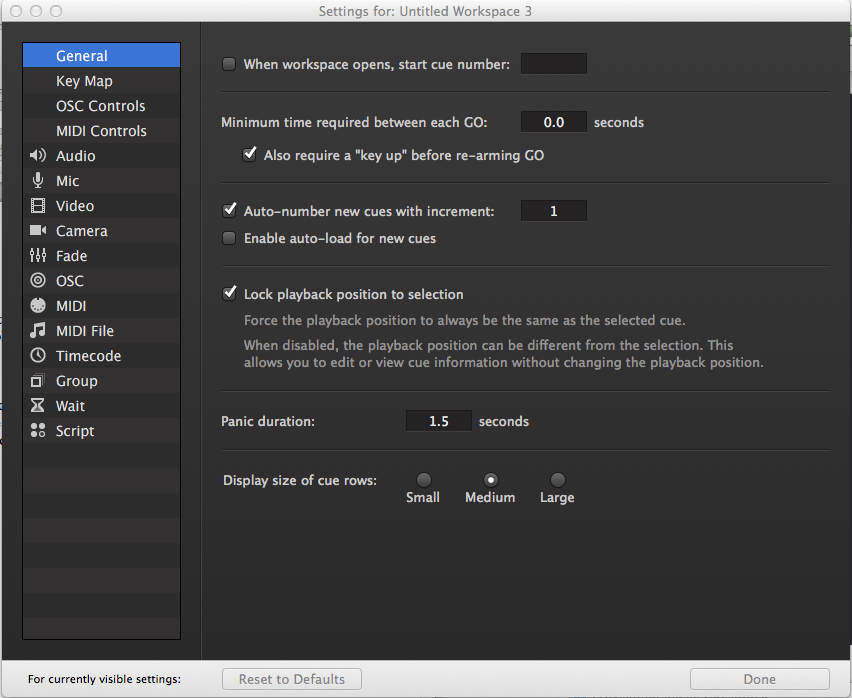

The folks at Figure53 (the makers of QLab) have some great (and free) resources. Their instructional videos are fun and user friendly, and you can follow along on a free version of QLab, as long as you have a Mac computer. Another super great Figure53 resource is the Figure53 Studio. There is a link on their website where they share experimental software for free! It should be noted that there is no support for these programs, so if you get stuck or have questions, you’re on your own. One of my favorite resources for learning and teaching QLab is the QLab Cook Book. This is a collection of QLab programming techniques and tricks developed by real-life QLab users! All three links are right here:

If you are located in or near Southern California, you will be able to take advantage of a super cool Yamaha resource I discovered about ten years ago. Yamaha has a program called “Audioversity” that offers all kinds of professional audio education and training activities. There is a healthy mix of self-paced training and instructor-led training. The folks at Yamaha are invested in education, and will happily give student tours of the Yamaha Corporation in Buena Park. It’s great for students to see new equipment that is being developed, and all of the cool things going on inside Yamaha. Check out this link for more info:

Whatever path you choose to use to introduce kids to audio, the important thing is to keep talking about it. It’s one of the technical areas of entertainment that often fades into the background, and that’s what makes it so scary to beginners. Audio is very accessible, and anyone can learn it. All it takes is a little patience and a great sense of adventure!