Keeping it Real – Section 2

This is Section 2 of Becky Pell’s 3 Section Article on Using psychoacoustics in IEM mixing and the technology that takes it to the next level. Section 1

Acoustic Reflex Threshold

Have you ever noticed how you and the band can take a break from rehearsing, come back half an hour later, and when put your ears back in everything feels louder? And then how after a few moments it settles down and feels normal again? It’s because of a reflex action of the stapedius muscle in the middle ear. When this little muscle contracts, it pulls the stapes or ‘stirrup bone’ slightly away from the oval window of the cochlea, against which it normally vibrates to transmit pressure waves to be converted into nerve impulses. This action, which is a response to sounds of between 70-100dB SPL, effectively creates a compression effect resulting in a 20dB reduction in what you hear. However, the muscle can’t stay fully contracted for long periods, so after a few seconds, the tension drops to around 50% of the maximum. Whilst the initial reaction, at 150 milliseconds, is not fast enough to fully protect the ear against very loud and sudden transient sounds, it helps in reducing hearing fatigue over longer periods. Interestingly this reflex also occurs when a person vocalises, which helps to explain why a singer’s in-ear mix of the band might sound loud enough in isolation, but when they start singing they find they need more instrumentation. This happens in conjunction with the fact they are hearing themselves not only via the mix but through the bone conductivity of their skull. It’s well worth trying to sing along to an IEM mix that you’ve prepared for a singer to experience what this feels like for them because it’s a very different sensation from simply shouting down the mic to EQ it.

The acoustic reflex threshold also means that transients appear quieter than sustained sounds of the same level, and it’s the thinking behind a compression trick that is often used in studios and film production. When you compress the decay of a short sound such as a drum hit, it fools the brain into thinking the drum hit as a whole is significantly louder and punchier than it is, although the peak level – the transient – has not changed. Personally, I’d advocate caution if you’re going to try this in a monitor mix – the drummer needs to hear what their drums ACTUALLY sound like, and getting things such as drum tuning and mic placement correct at source are vital – but it’s an interesting thing to be aware of.

All in the timing

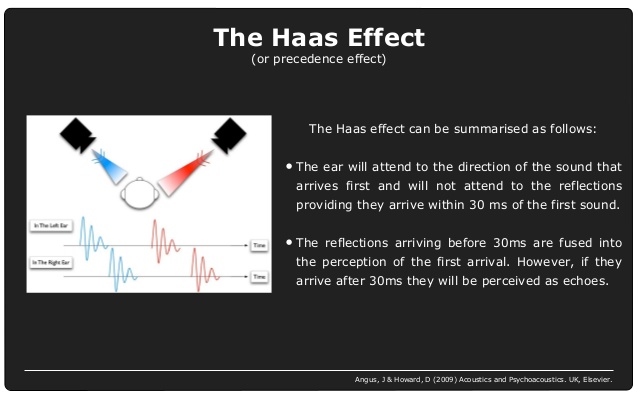

Our ability to perceive sounds as separate events is not only dependent on there being sufficient difference between them in frequency, but also on timing. This phenomenon is known as the ‘precedence effect’ and the ‘Haas effect.’

These effects describe how when two identical sounds are presented in quick succession, they are heard as a single sound. This perception occurs when the delay between the two sounds is between 1 to 5 ms for single click sounds, but up to 40 ms for more complex sounds such as piano music. When the lag is longer, the second sound is heard as an echo. A single reflection arriving within 5 to 30 ms can be up to 10 dB louder than the direct sound without being perceived as a distinct event. In 1951 Helmut Haas examined how the perception of speech is affected in the presence of a single reflection. He discovered that a reflection arriving later than 1 ms after the direct sound increases the perceived level and spaciousness (more precisely, the perceived width of the sound source), without being heard as a separate sound. This holds true up to around 20ms, at which point the sounds become distinguishable.

This can be an interesting experiment to try with a vocal mic and your IEMs. If you split the vocal mic down two channels, and delay one input somewhere between 1 and 20 ms, see what you notice. Then try panning one input hard left and the other hard right, and see how the vocal sounds thicker and creates a sense of width and space. Play with the delay time, and you’ll see that if it’s too short the signal starts to phase; too long and you lose the illusion. This game does make the signal susceptible to comb-filtering if you sum the inputs back to mono, especially at shorter delay times, so be aware of that.

Once again I would advocate extreme caution if you intend to use this in a monitor mix, as ‘tricking’ a singer in this way can backfire! However it’s a useful principle to be aware of if you have the opportunity to get creative with other sounds, and I use it a lot when adding pre-delay to a reverb – try it for yourself. No pre-delay creates a feeling of immediacy to the effect, but just 5-10ms creates a slight sense of space. If you’re after a little more breathiness and drama – ‘vampires swirling’ as I once heard it described – try increasing the pre-delay up to 20 ms and feel how it changes.

The Haas effect is also something to be very aware of for IEM mixing when it comes to digital latency. Every time we take a signal out of the console and send it somewhere else in the digital domain, a degree of minor time delay known as latency is introduced. Different processing devices introduce different amounts of latency, and obviously the less, the better. The more devices we add, the more the latency stacks up. Whilst a few milliseconds of latency may be totally imperceptible for, say, a guitarist; it’s a different matter when it comes to vocals. A singer will often be able to perceive something as being not quite right, without being able to put their finger on it, because when we vocalise and have that signal returned to our ears, the discrepancy between what we hear at the moment of making the sound, and the moment of it returning, becomes heightened in our awareness. Something to be vigilant about when dealing with any digital outboard such as plug-ins, for a singer.

Location Services

The Haas effect also affects where we perceive a sound to be coming from – the supposed location of the source is determined by the sound which arrives first, even though the sounds may be from two different physical locations. This holds true until the second sound is around 15dB louder than the first when the perception of direction changes.

Sound localisation is a very complex mechanism performed by the human brain. It’s not only dependent on the directional cues received by the ears, but it is also intertwined with the other senses, especially vision and proprioception. Our ability to determine a sound’s location and distance is called binaural hearing, and in addition to all the psychoacoustic effects discussed so far, it is also heavily influenced by the physical shape of our heads, ears, and even torsos. The outer ear or ‘pinna’ functions as a directional sound collector which funnels sound waves into the ear canal. The head and the topography of our face and torso influence how sounds from any position other than a 0° angle are heard, as they create an acoustic ‘shadow.’ Our brains process the differences between the information that our two ears collect, and interpret the results to determine where a sound is coming from, how far away it is, and whether it’s still or moving. At lower frequencies, below about 2kHz, this is mostly determined by the inter-aural time difference; that is, the discrepancy in time between when the sound reaches each ear. Above 2k the information gathered comes from the inter-aural level difference; that is, the discrepancy in volume between the sound that each ear hears. This clever evolutionary adaptation is due to the relative lengths of sound waves at different frequencies. For frequencies below 800 Hz, the dimensions of the head are smaller than the half wavelength of the sound waves so that the brain can determine phase delays between the ears.

However, for frequencies above 1600 Hz the dimensions of the head are greater than the length of the sound waves, so a determination of direction based on phase alone is not possible at higher frequencies; instead, we rely on the level difference between the two ears. These binaural disparities are known as Duplex theory and play an important role for sound localisation in the horizontal plane.

(As the frequency drops below 80 Hz it becomes difficult or impossible to use either time difference or level difference to determine a sound’s lateral source because the phase difference between the ears becomes too small for a directional evaluation, hence the experience of sub-bass frequencies being omnidirectional.)

Whilst this phenomenon makes it easy to sense which side a sound is coming from, it’s harder to determine direction in the up/down and front/back planes, due to our ears being placed at the same horizontal level as each other. Some types of owl have their ears placed at different heights, to allow for greater efficiency in finding prey when hunting at night, but humans have no such facility. This can result in ‘cones of confusion’, where we are unsure as to the elevation of a sound source because all sounds that lie in the mid-sagittal plane have similar inter-aural differences; however, once again the shapes of our bodies help us out. Imagine a sound source is right in front of you. There is a certain detour the torso reflection takes and hence a certain difference of this torso reflection in relation to the direct sound arriving at both ears. This yields a slight comb filter pattern which will change if you elevate this source. The same is true if this source is now moved behind you; the torso reflection changes and our brains process the information discrepancies to help us locate the source.

Next time: In the third and final section of this series on using psychoacoustics to enhance your monitor mixing, we’ll discover a ground-breaking new technology that takes IEMs to a whole new dimension.