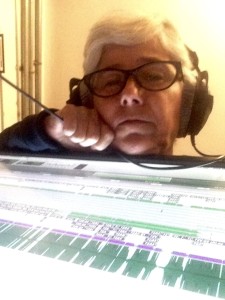

Mix Messiah – Leslie Gaston-Bird

Leslie Gaston-Bird is a freelance re-recording mixer and sound editor, and owner of Mix Messiah Productions. She is currently based in Brighton, England and is the author of the book “Women in Audio“. She is a voting member of The Recording Academy and sits on these AES committees: Board of Governors, Awards, Conference Policy, Convention Policy, Education, Membership, and Co-Chairs the Diversity & Inclusion Committee with Piper Payne. She was a tenured Associate Professor of Recording Arts at the University of Colorado Denver. Leslie also is Co-Director for SoundGirls U.K. Chapter and SoundGirls Scholarships and Travel Grants. She has worked in the industry for over 30 years.

Leslie Gaston-Bird is a freelance re-recording mixer and sound editor, and owner of Mix Messiah Productions. She is currently based in Brighton, England and is the author of the book “Women in Audio“. She is a voting member of The Recording Academy and sits on these AES committees: Board of Governors, Awards, Conference Policy, Convention Policy, Education, Membership, and Co-Chairs the Diversity & Inclusion Committee with Piper Payne. She was a tenured Associate Professor of Recording Arts at the University of Colorado Denver. Leslie also is Co-Director for SoundGirls U.K. Chapter and SoundGirls Scholarships and Travel Grants. She has worked in the industry for over 30 years.

Leslie has done research into audio for planetariums, multichannel audio on Blu-Ray, and a comparison of multichannel codecs that was published in the AES Journal (Gaston, L. and Sanders, R. (2008), “Evaluation of HE-AAC, AC-3, and E-AC-3 Codecs”, Journal of the Audio Engineering Society of America, 56(3)). She frequently presents at AES conferences and conventions.

She has been working in the industry for over 30 years: 12 years in public radio, 17 in sound for picture, and 13 years as an educator (some of these years overlap). Her interest in sound for film was sparked by seeing Leslie Ann Jones on the cover of Mix Magazine in the 1980s. She attended Indiana University Bloomington and graduated with an A.S. in Audio Technology and a B.A. in Telecommunications. While she was at Indiana University Bloomington, she signed up for a work-study job as a board operator at the campus radio station, WFIU-Bloomington. This gave her the skills she needed for her first job, which was at National Public Radio in Washington, D.C.

She has been working in the industry for over 30 years: 12 years in public radio, 17 in sound for picture, and 13 years as an educator (some of these years overlap). Her interest in sound for film was sparked by seeing Leslie Ann Jones on the cover of Mix Magazine in the 1980s. She attended Indiana University Bloomington and graduated with an A.S. in Audio Technology and a B.A. in Telecommunications. While she was at Indiana University Bloomington, she signed up for a work-study job as a board operator at the campus radio station, WFIU-Bloomington. This gave her the skills she needed for her first job, which was at National Public Radio in Washington, D.C.

Leslie worked at NPR from 1991-1995 as their audio systems manager. She recorded and edited radio pieces and did a ton of remote recording and interviews on DAT tape. (Who remembers DAT tape?) From NPR she went on to work for Colorado Public Radio as their Audio Systems Manager.

Although Leslie loved working for both NPR and Colorado Public Radio, her passion was sound for film, and it was not easy for her to get her foot in the door. It took her over four years to find someone who would take a chance on her. Her gratitude for this opportunity goes to Patsy Butterfield, David Emrich, and Chuck Biddlecom at Post Modern Company in Denver.

Leslie still works as a freelancer in Film Sound and has currently been working on several horror films and thrillers. “For some reason, I keep getting horror films to work on. I recently did the sound for Leap of Faith, a documentary about The Exorcist which has been selected for the Sundance Film Festival in 2020. Also coming out is A Feral World, a post-apocalyptic tale of survival about a young boy who befriends the mother of a missing girl. It’s not a horror film but there are a few violent scenes. I also did sound for Doc of the Dead, a documentary about zombies and zombie culture. The plot for the current film I’m working on, Rent-A-Pal, is one I’m not at liberty to disclose, but suffice it to say there’s a pattern here. However, I have also done some great documentaries focused on peace and harmony, too! Three Worlds, One Stage featured a woman directing/producing team (Jessica McGaugh and Roma Sur of Desert Girl Films) and told the story of three people from different cultures who moved to the United States and choreographed a dance together, and Enough White Teacups (directed by Michelle Carpenter) which explores the winners of the Index design awards which recognize innovations designed to improve the human condition. Michelle also did Klocked, a story of a mother-daughter-daughter motorcycle racing team. I’m proud to have worked on these woman-powered projects.”

Leslie still works as a freelancer in Film Sound and has currently been working on several horror films and thrillers. “For some reason, I keep getting horror films to work on. I recently did the sound for Leap of Faith, a documentary about The Exorcist which has been selected for the Sundance Film Festival in 2020. Also coming out is A Feral World, a post-apocalyptic tale of survival about a young boy who befriends the mother of a missing girl. It’s not a horror film but there are a few violent scenes. I also did sound for Doc of the Dead, a documentary about zombies and zombie culture. The plot for the current film I’m working on, Rent-A-Pal, is one I’m not at liberty to disclose, but suffice it to say there’s a pattern here. However, I have also done some great documentaries focused on peace and harmony, too! Three Worlds, One Stage featured a woman directing/producing team (Jessica McGaugh and Roma Sur of Desert Girl Films) and told the story of three people from different cultures who moved to the United States and choreographed a dance together, and Enough White Teacups (directed by Michelle Carpenter) which explores the winners of the Index design awards which recognize innovations designed to improve the human condition. Michelle also did Klocked, a story of a mother-daughter-daughter motorcycle racing team. I’m proud to have worked on these woman-powered projects.”

While Leslie was working at Post Modern at night, she was also pursuing a Masters Degree and her professors encouraged her to apply for a teaching position. She did and ended up as a tenured professor at the University of Colorado Denver, where she taught until 2018 when she relocated to Brighton, England. She was also encouraged by her professors the late Rich Sanders and Roy Pritts to join the AES where she became heavily involved.

“It has opened so many doors. I met Dave Malham at an AES convention in San Francisco and he ended up being my sponsor for a Fulbright Award at the University of York, England. I have done lots with AES, from being secretary of my local section to chair, then Western Region VP and Governor. In 2016 Piper Payne helped me to start the Diversity and Inclusion committee which we co-chair. We have come a long way, most recently partnering with Dr. Amandine Pras at the University of Lethbridge for their “Microaggressions in the Studio” survey. I’m really proud of the changes we have made, the AES Convention in New York was proof of our impact, with high visibility of women and underrepresented groups on panels, presenting papers and workshops, and even in the exhibit floor. In my 15 years of attending conferences I’ve never seen anything like it and we received so much positive feedback. We have more work to do but we have every reason to be proud of these accomplishments.”

In 2018, Leslie and her family relocated to Brighton, England, to be closer to her husband’s family (he is British) and it looks like they will be there for the foreseeable future. In addition to running her own business, her work with AES, writing Women in Sound, a (did we mention she is starting a Ph.D.?) Leslie is the mother of two children. She balances it all by being highly organized and managing her time well. She says, “Somewhere I read that mothers of siblings are more productive. I think it’s because you have to be focused when you work. I think to myself, “okay, I only have 3 hours to do x-y-x” and I’m on it! No time to procrastinate! It’s not easy but in ways, it’s better because you learn the value of budgeting time and focusing on the task at hand.”

Leslie has a book coming out in December, Women in Audio and she shares the experience of writing it and the importance of it:

“More than anything, I hope this book is a testament to my commitment and indebtedness to the women who have trusted me with their stories. I must say, I have been nervous at times because the weight of these stories is truly immense; women whose stories might otherwise go untold are brought to light here. I have found so many pioneering women throughout history: inventors, record producers, acousticians I’ve tried to cover every field of audio I could. Altogether there are around 100 profiles. It’s really a must-have for women and girls seeking inspiration; for schools who want to add diversity to their curriculum (I took care to seek out women from all over the globe); for professionals who may think they’re the only woman in their area of expertise. I also talk about role models, mentoring, and networking. I’m really looking forward to sharing it with everyone!”

With a career spanning over 30 years, working in several roles as Educator, Mixer, Musician/Talent, Production Sound Mixer/Sound Recordist, Recording Engineer, Re-Recording Mixer, Researcher, Sound Supervisor, and Author; you would think Leslie is ready to rest on her laurels, but no, in 2020 at the age of 51 she will begin her Ph.D. at the University of Surrey.

What do you like best about working in Film Sound?

What I like most about working on films is the meditative rhythm of finding and selecting sounds, shaping the sounds, and giving the film a sense of realism.

What do you like least?

The thing I like least is computer crashes. It’s the rise of the machines – they are training us.

What is your favorite day off activity?

Hanging out with my kids.

What are your long term goals?

I have written a book on Women in Audio, which I hope to follow up with another volume. There are so many amazing women in Women in Audio: 1st Edition (Paperback) all sorts of audio fields, and it is an honor to share their stories. I would also like to continue supporting women to travel to and attend conferences with the fund I set up with SoundGirls.

What if any obstacles or barriers have you faced?

Moving to England and leaving a tenured position at a university was equal parts confidence and insanity. I have always believed in risks, but at age 50 I still feel the need to prove myself. I’m planning to start a Ph.D., but I have a feeling that women – more than their male counterparts – feel the need to seek higher academic qualifications in order to compete in the job market. It’s something I hope will change.

How have you dealt with them?

Well, by applying for a Ph.D. I’ve been accepted at the University of Surrey and will start in 2020, the year I turn 51.

The advice you have for other women and young women who wish to enter the field?

Stay versatile and stay connected.

Must have skills?

You can always train your ears and learn the equipment, but the most valuable skills are creativity, diplomacy and client service.

Favorite gear?

Loudspeakers: Genelec, PMC. Preamps: Grace, Neve 5012.

Parting Words:

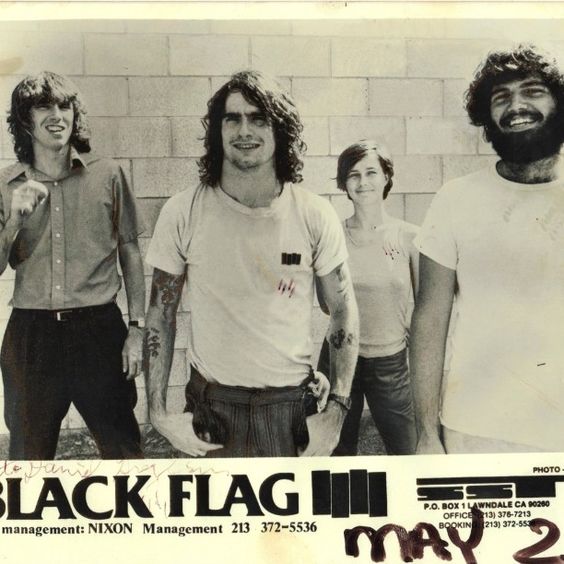

I suppose one thing I’d like readers to know about is a moment I had recently, standing in my dining room, looking over some pictures that I had received from a man named Dana Burwell. The pictures were of Joan Lowe, a recording engineer that worked on some feminist albums in the 1970s (The Changer and the Changed, among others). Joan Lowe did not have family, and these pictures were entrusted to me for the purposes of writing the book, Women in Audio. The only reason Dana knew me was because I had reached out to Joan in November to interview her for the book. Joan had emailed me answers to my questions but passed away in February. If I hadn’t been in touch with Joan, I wonder what would Dana have done with those photos?

So there I was, standing in the living room, with pictures of a very friendly woman who I just met, who shared her story with me – and who trusted me with her story – and who passed away a short while later. I now had the duty to share her story. It’s a responsibility I haven’t taken lightly. On that day it happened to be sunny. I looked up at the sky, and thanked Joan, with an expression on my face that was a combination of awestruck and joyful. I continued writing with a renewed passion that day. Something else in me changed, too, but I’ll leave that for another interview. In the meantime, it’s an honor and a privilege to bring these stories to our audio community.

More on Leslie

- The SoundGirls Podcast – Leslie Gaston-Bird: Author, AES Board of Governors, and owner of Mix Messiah Productions

- Women in Sound – Leslie Gaston-Bird

- NAMM – Leslie Gaston-Bird

- Women in Audio The Book

- You can read more about Leslie and her accomplishments here